Recently the ATO released its annual statistics for the most recent tax year. You can find all sorts of statistics in the release here. I decided it was about time I updated anything I could find on actuarial pay, and particularly gender gaps. A couple of years ago, Julia Lessing did a guest post here on whether there really is a gender pay gap, and what might be behind it. That was based on the previous ATO data. What can we find out now?

Yes there is a gender pay gap for actuaries

If you look at the statistics for Financial Year (FY) 2017, a male tax paying actuary earned gross income (before tax) on average 39% more than the average female tax paying actuary. That’s less than the overall average of 49% across the tax paying population but it definitely isn’t equality.

I expect that I will immediately have objections from my audience; am I comparing like with like? As Julia reported in her previous article, female actuaries are more likely to be part-time, to be younger, and less senior. But it is unarguable that female actuaries, on average, earn less than male actuaries.

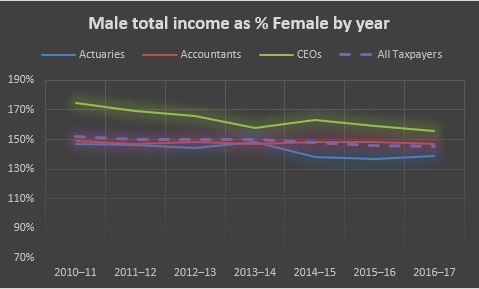

The graph shows that this difference is (for actuaries) decreasing gradually over time. In FY11, male actuaries earned an average of 49% more than their female counterparts rather than the 39% in FY17.

I thought it would be interesting to look at a few other professions. The gap for CEOs is much bigger, and the gap for accountants started out the same, but has stayed higher.

Has anything changed in the latest statistics?

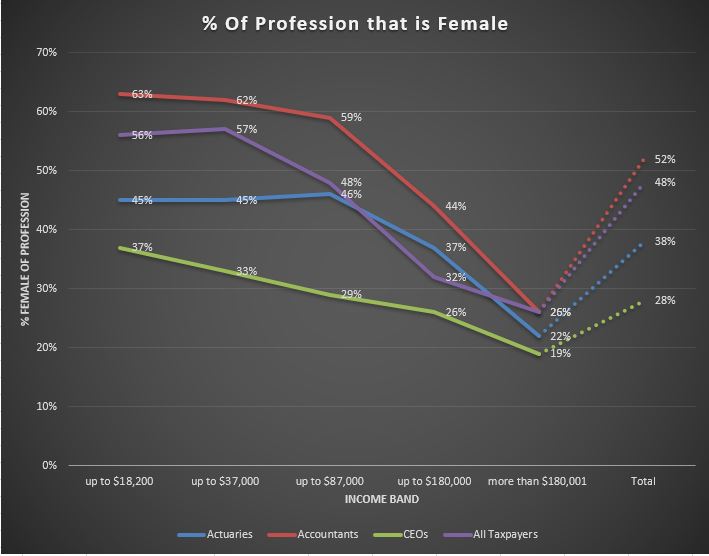

So let’s take a closer look at the most recent year of FY17. The proportion of women in the lower salary bands is much higher than the proportion of women in the highest salary band. That difference is true for all of the professions I looked at, but probably the steepest for the accountants. Actuaries have a more gradual differential, with 37% of the lowest paid actuaries being female, compared with 19% of the highest paid.

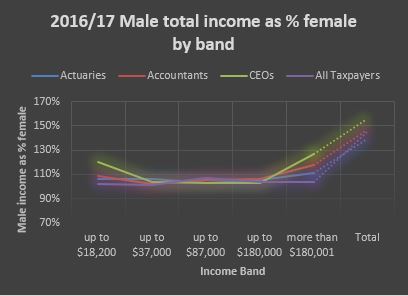

And within those individual salary bands, the gap is not as large. Most of the gap seems to be due to the much greater proportion of men in the highest possible salary band.

We don’t have enough statistics here to draw firm conclusions of the underlying causes of the gender pay gap for actuaries. So a few possible causes:

- Women are more likely to be part time/ out of the workforce. That is supported by the greater proportion of women in the two salary bands up to $37,000 (which for actuaries is a part time income).

- Female actuaries are on average younger than men. This one is supported by Nicolette Rubinsztein’s recent Presidential Address in which she points out that actuarial Fellows with more than 15 years experience are only around 20% female, compared with more recently qualifed Fellows who are around 30% female.

- Male actuaries are general in more senior roles than women. This one is supported very much by the data of proportions at the highest income levels; an income of more than $180,000 generally requires seniority for an actuary, not just qualifications.

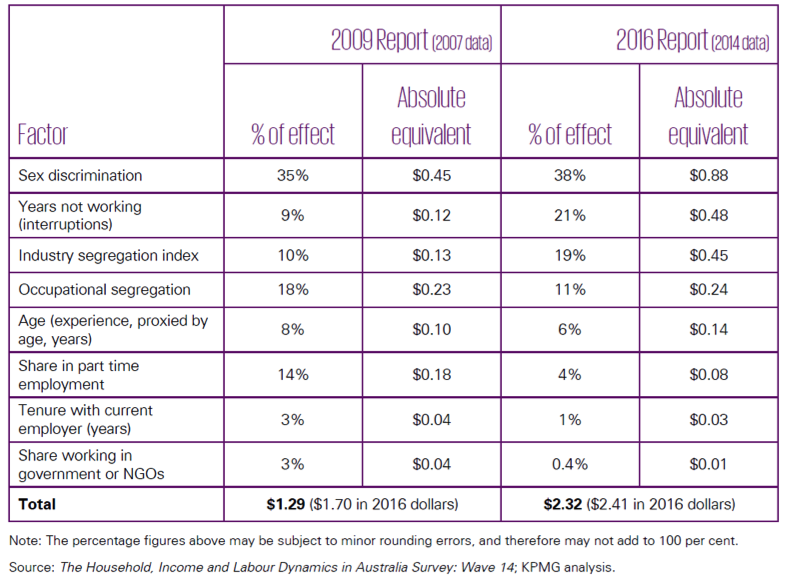

- And the remainder – some proportion is probably due to fundamental prejudice. My experience suggests that for roles that are graded the same, in a given organisation, it is rare for women to be paid less than men. However, the sexism is likely to creep in in the grading and the promotion and appointment experience. This is part of the reason that male actuaries are generally in more senior roles than women. There is enough evidence from many different economic papers that sexism in the appointment etc process exists to make this a plausible explanation for some of the gap. KPMG did a large study on this point in 2009, which they updated in a 2016 report. This shows that a significant part of the total pay gap for full time workers (ie after correcting for number of hours and experience) is still due to sex discrimination.

Why does this matter?

Generally sex discrimination is by far the easiest to analyse, as the data is available. Discrimination on other lines (parenthood, ethnicity, sexuality, religion etc) is much harder to analyse, as most data sets do not include categorisation on any basis other than gender.

My view, though is, that if sex discrimination exists, all those other potential sources of discrimination probably do too. So it is worth analysing not just for its own sake, but for the sake of all groups subject to discrimination.