I wanted to do some interesting analysis of who is getting vaccinated in Australia, in the different categories, now that more than 4 million doses have been delivered. But I can’t. Why not? Because unlike every other rich country I have randomly googled, very little data is publicly available. So instead, I’ve looked at what data other countries have been tracking, and why it would help our rollout.

Anthony Macali, who maintains my favourite statistics site on all things Covid19 in Australia, is doing his best. And that best is so good that he reverse engineered a measure of how many people have had a second dose (check out the complex way he did this using code from WA Health’s public graphs) in his twitter thread here.

Despite many requests, it’s clear @healthgovau and @GregHuntMP do not want to publish second dose data. But I found a way and this is how.

Last week @WAHealth released this vaccince dashboard.https://t.co/RO0Ljig8KC pic.twitter.com/nnL1OOISnq

— Anthony Macali 🔌⚡ (@migga) May 27, 2021

Back in March, when Australian vaccinations were just starting, Macali tweeted a simple request for data:

- Doses administered

- People fully vaccinated

- Doses allocated

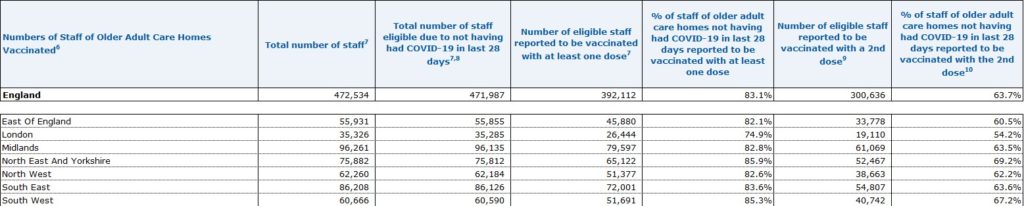

Macali is totally right, and it is shocking that this information is still not available. But we need much more data than that to understand how well our rollout is going. In the UK, very granular data is published weekly, including by dose, age, ethnicity, local authority, two types of care homes (residents and staff separately), health care workers, and at risk individuals and carers.

Here’s a screenshot of a table of aged care staff vaccination rates in England, as just one of many possible examples that is available every week.

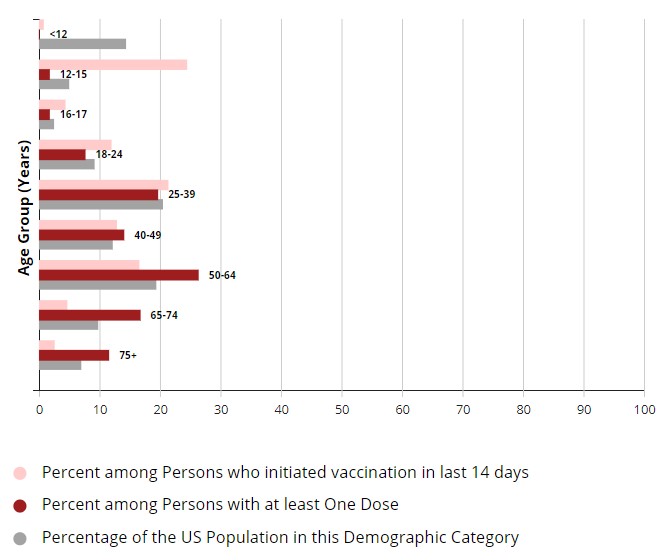

In the US, the CDC site allows you to play around with different graphs by region, age, ethnic background – here is a fairly basic graph showing the percentage of each age category who have been vaccinated with at least one dose.

Why does this actually matter? Tim Harford, one of my favourite economic authors has an important rule about numbers (one of his 10 rules of how to make the world add up):

Don’t take statistical bedrock for granted.

It’s possible to lie and obfuscate with numbers, but can you imagine making tough decisions without data? We need to be cautious about statistics, but we shouldn’t forget to appreciate them and those who gather and crunch the data to produce them.

“All around us, statisticians and other hero-geeks are painstakingly gathering and analyzing the numbers we need to understand what is happening all around us,” Harford writes, citing all the scientists rushing to get a handle on the current pandemic as one extremely topical example.

“The statistics are quietly and carefully assembled and we take them for granted. We just assume they will always be there when we need them. We notice only when something goes wrong. That is a shame. So let us celebrate the wonderful folks who help us see the invisible all around us,” he urges.

In the case of vaccines in Australia, I don’t know whether the data has been assembled and is not being shared, or whether it doesn’t exist. Either way, that is a problem.

Because if we (and that is the government, and those in the media and the public holding the government to account) aren’t measuring vaccine take-up, we don’t know what is working and what isn’t.

I have some theories about who is taking up vaccines right now and why it is slower than most of the world. So do most of the people I talk to. None of us have any idea beyond anecdote whether we are right. And without understanding what is going wrong, it is pretty hard to fix it. I would like to think that the numbers I would like to see are being tracked inside government, but the very vague way they are talked about when the media asks makes me suspect that those numbers aren’t being tracked anywhere.

It’s a cliché, but what gets measured gets done. And if we measure where and which people are being vaccinated, we can work out where it is not happening and fix it.

The more granular our information about vaccination rates (age, ethnic background, location, aged care workers etc) the more everyone can understand what needs to change to make it faster.

If you read this article about “Vaccine hesitancy” it talks about how many factors other than reluctance to be vaccinated go into the end result of a population being vaccinated or not:

Hesitancy can become a tempting explanation for low vaccine coverage when governments seek to deflect attention from health system problems. For news editors, a story about a person rejecting vaccination because of their beliefs is probably more interesting than reporting a more prosaic lack of transport or inconvenient clinic hours.

But which one is most important? The article goes on:

Behavioural scientists have reviewed studies to find the interventions with the largest impact on vaccine uptake. Those most effective include: making vaccines free and services convenient, reminders when a vaccine is due, default appointments, performance monitoring and feedback, on-site vaccination, standing orders, incentives and requirements.

Educating and informing people on its own does not usually improve uptake, except where a new campaign seeks to inform and motivate people about a new vaccine.

Which of these factors is most important in Australia right now? Good question. It is not a coincidence that the UK, one of the most comprehensive vaccination rollouts in the world, also has excellent data. Australia should be doing the same.

Links

Still on vaccination, this article in the New York Times explains why vaccinating the world (not just rich countries) is the best investment ever:

The I.M.F. calculates that an urgent $50 billion investment — now! — primarily by rich countries to vaccinate people in poor countries would yield an astonishing $9 trillion in additional economic growth by 2025, by controlling the pandemic earlier.

That would be a return of about 267 percent per year over four years, according to experts I spoke to. In contrast, an Oxford University study found an average return from private equity of just 11 percent per year.

But even if the I.M.F. estimates of benefits are off by an order of magnitude, so that the gain is only $900 billion rather than $9 trillion — that’s still an extraordinary 18-fold return on a $50 billion investment. The West can’t afford not to make it.

And this tweet from Dr Eric Topol shows that vaccines are generally (so far) effective against all the variants that have been identified, although in some cases, two doses are required and/or the vaccine only protects against severe disease.

If you can, get vaccinated!

Life Glimpses

Definitely a swings and roundabouts set of glimpses in this post.

So I’ve now been vaccinated with Astra Zeneca, at a nearby GP clinic (not my usual doctor since they didn’t have doses). The actual vaccination was very straightforward, but finding an available slot did take me a few goes at checking all the local clinics for availability – say a couple of hours of research off and on. Luckily, I live in an area with lots of GPs, and I have time to go a reasonable distance and be flexible about my appointment time.

Sadly, my trip to Melbourne next week (which was a mix of work and pleasure) has been cancelled and replaced with some zoom meetings. A slight inconvenience for me, much worse for those in Melbourne who are locked down yet again.

And my choir is now meeting weekly in person in our local church hall, and is doing our own individual tracking of vaccinations among our members.

Bit of beauty

So many choices of beautiful pictures since my last post – sunsets, autumn leaves, lakes (sometimes all three in one picture), but I couldn’t go past these mushrooms from our local street, snapped by geekinsydney last week.

“why it is slower than most of the world” is inaccurate. While the rollout in Australia is well behind Europe and the US (where the mRNA vaccines were developed, and so who had the headstart on rollout), we are ahead of countries like Japan, South Korea, New Zealand, India etc.

I had my AZ vaccine over a week ago, and it was showing up in my Medicare app a couple of days later. Since the vast majority of recipients will have a medicare number, I’m pretty confident the numbers are available to those who need them, with a breakdown by age, gender and location.

Until our supplies begin to exceed demand, I don’t see an urgency in trying to combat vaccine hesitancy.

The vaccination numbers I’d be most interested in seeing would be the percentage of international arrivals

Thanks Gary, my measure of compared to the rest of the world is as a % of population – the World as a whole is currently showing just under 25 doses per hundred people, whereas Australia is 16.6 doses per hundred people (according to our world in data).

But Australia has over 15% partially or fully vaccinated against 11% for the world. There’s certainly a narrative that we are ‘slow’ but the reality is there are some nations, mostly with very high numbers of deaths, that are way ahead in the rollout, Australia somewhere in the middle, and a large number of countries behind. However our position is more reflective of the fact we started later that the leaders.

Our choice to not use AZ for the under 50s means that it won’t be possible to achieve high vaccination coverage until the end of the year regardless of how steady or varied a pace we manage in the meantime

I think we’ll have to agree to disagree. Yes there are countries that are slower than Australia, some of them rich, but my view is that you need quite a few qualifications (such as starting late, using AZ for under 50s, low death rates) before you can look at Australia and see anything other than a slow rollout.

But that isn’t the main point of my post. My point is that without better data, we don’t really understand why this rollout is slower than originally targeted, and slower than I (and I think many others in Australia) would like. All we can do is theorize based on anecdote.