Today’s Book Review is Men at Work: Australia’s Parenthood Trap, the latest Quarterly Essay by Annabel Crabb

In a follow up essay to her previous book The Wife Drought, Annabel Crabb investigates what is stopping men taking on more of the parenting load.

In the last 50 years, women have massively changed their work patterns in Australia, by moving into the workforce in large numbers. But, by and large, men have not changed their work patterns to share the load at home more. Why is that? Is it that, as often depicted in stereotypical TV commercials, fathers are no good at it, and would rather spend the time at work? Or is it that the way society and work is structured makes it much harder for them to participate in home life in the way that mothers are expected to?

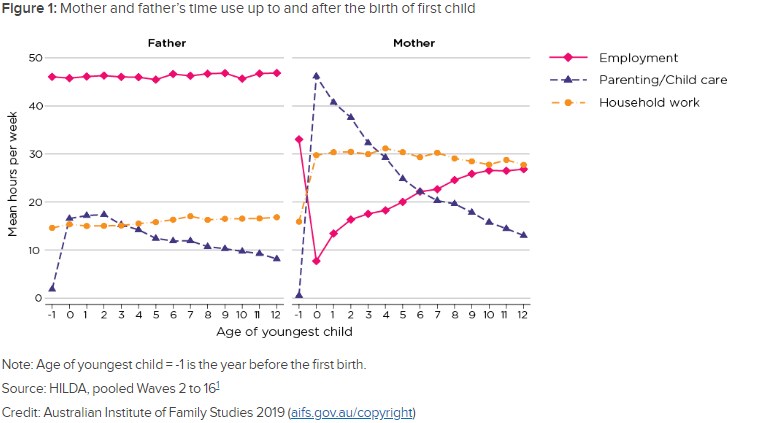

Crabb illustrates the problem she is trying to understand with a stunning graph from Jennifer Baxter’s research into fathers and work. After the birth of their first child, on average, fathers’ employment and household work hours do not change. Whereas on average mothers’ household work doubles and stays twice as high, and their employment hours take a massive drop which is not recovered even by the time the child turns 12.

After shocking her reader with that graph, Crabb goes on to try and investigate the causes of this massive discrepancy. And what she finds is that there are a lot of fathers who would quite like to share in the parenting and household work load. But there are forces lined up against them, both in workplace cultures, and also in the financial structures set up to support parenting.

What she finds is a combination of culture and rules that make it hard for men to take advantage of the various possibilities of flexible work that women use as a matter of course in many workplaces in Australia.

For flexible work, she finds that the men who she talks to feel much less entitled to use flexibility to (for example) spend time at the reading group at school, or the swimming carnival. They are much more likely to feel that they need to prove their extraordinary worth as an employee first.

“Flexism” – discrimination against workers who would like to work flexibly – is a term of increasing currency. And men who ask for flexible work are twice as likely to have their request refused as women, according to a 2016 study by business consulting group Bain and Company.

In my own working life, I’ve tried to create an environment for men as well as women to work flexibly. But when I count it up, the balance is pretty skewed. In teams that I have led, I’ve had three men work part time so that they can spend time with their families. I’ve had two men take extended parental leave as the primary carer. And I can’t count how many men have used working from home or shifting their hours to help with the school pick ups and/or drop offs.

But right now, in my team, there are 12 people working part time. Only one of them is male. And compared with the two men I vividly remember taking extended parental leave, I’ve lost count of the women in teams I’ve led who have taken extended parental leave. So my supportive management is not enough – the structures and company cultures have to change too.

Currently the structures are set up to push mothers to take what flexibility there is. As Crabb points out,

The person who takes the leave invariably becomes the person who knows more about nappy-changing, more about which food the kid likes, more about nap times and play dates and which kids at the park have nut allergies.

Crabb points out that while the language of parental leave is superficially gender neutral (“parental leave”, “primary carer”) the clear assumption from everyone, employers and employees, is that the birth mother takes the parental leave, paid and unpaid, and stays the primary carer. And if you are not the sole carer of your child, the paid parental leave (or unpaid leave when the parental leave runs out) is not available to you.

Crabb gives the example of Medibank, which has formally abolished the notion of “primary carer” and “secondary carer” in its parental leave scheme.

On International Women’s Day, the insurer revealed it would offer fourteen weeks’ leave at full pay that either parent could take any time in the first two years of their child’s life… the company would allow parents to take the leave in one chunk, or two – or even use it to work part-time over the two years.

That increased the proportion of men taking parental leave from 2.5% to 28% of all parental leave. I must admit I was quite sceptical of this concept. I couldn’t help wondering how many dads were taking the leave at the same time as their spouses, and not necessarily participating equally in all the work that comes with new parenthood (perhaps getting in a few golf games?).

But the more I think about it, the more it makes sense. Whether or not it is an equal partnership (and really that is no-one’s business but the couple in question), research shows repeatedly that fathers who are deeply involved in their child’s early life are much more likely to stay involved and share the care equally later on. And that seems like a good thing for everyone to me – the children (who have a stronger relationship with both parents), the mothers (who have more support at home and to enable them to have a life outside the home) and the fathers, who benefit from being much more fundamentally part of their family’s life than just being the breadwinner.

To make a big change in sharing at home, there needs to be something structural. Many more fathers would like flexibility than currently get it. More ability to share parental leave, as Medibank does, could be a real cultural change, if other big companies start copying it.

It’s always a pleasure reading Annabel Crabb’s writing. But I particularly liked the tone of this essay. Crabb isn’t interested in casting blame on anyone for how parenting is shared. She’s interested in helping men have more choices in the way they participate in their families than they have right now. Recommended.