I’ve just published my annual reading list for 2024 here, as I’ve done for over a decade. Do check out the whole thing, but here are a few of my particular favourites from this year’s list, which, as always, is a bit of an eclectic mixture.

How Big Things Get Done: The Surprising Factors Behind Every Successful Project, from Home Renovations to Space Exploration, by Bent Flyvbjerg and Dan Gardner

How Big Things Get Done: The Surprising Factors Behind Every Successful Project, from Home Renovations to Space Exploration, by Bent Flyvbjerg and Dan Gardner

This was my favourite book this year. Flyvbjerg has made a career of analysing big projects, starting in Denmark with big construction projects, and then moving ever wider, both geographically and type of project. With a mixture of storytelling and didactic lessons, he and his coauthor Gardner use their experience and analysis of all these projects to take out a pithy set of lessons about how best to make big projects work as intended.

This book is full of insights, many of which I have bored friends, family and colleagues with this year. It is structure around the stories of good projects (the Bilbao Guggenheim) the bad (the Sydney Opera House), and the ugly (California High Speed Rail). But the real gold is in the 11 heuristics for better projects, that the book finishes with.

- Hire a masterbuilder – always start with someone with deep experience in a project very like the current project

- Get your team right – I think this lesson is deeply underrated. A team that has worked together on project after project in any field is always better than a team of superstars assembled for the first time.

- Ask Why – the purpose for any given project might not be the public one – the Guggenheim in Bilbao is a great example of this. The purpose was not an art gallery, it was a building to put Bilbao (a declining industrial town) on the map.

- Build with Lego – prototype as much as humanly possible before you start

- Think slow, act fast – this one seems obvious, but the world is littered with mistakes that seem obvious in retrospect that weren’t recognised in advance

- Take the outside view – find the class of projects that your project belongs to and learn from it, don’t think that your project is unique and special (this is a particular problem for the Olympics, and probably why they are some of the worse overrunning projects)

- Watch your downside – think really hard about all the risks and mitigate them, rather than just adding budget for them

- Say no and walk away – the most successful project managers don’t take on everything they are offered

- Make friends and keep them friendly – a big project has stakeholders everywhere, many of whom can massively disrupt a project if they are not happy. They are part of the job, not just a distraction

- Build climate mitigation into the project – this is both about understanding risks (which have increased with climate change) and doing your part not to make it worse

- Know that the biggest risk is you – hubris – thinking that you won’t make all the mistakes everyone else has made.

This book is a highly readable analysis by authors who really, deeply know their stuff – those lessons are much more impactful after reading the stories that go with them. Should be compulsory reading for anyone who involved with a big project.

Age of the City, why our future will be won or lost together, by Ian Goldin and Tom Lee-Devlin

Age of the City, why our future will be won or lost together, by Ian Goldin and Tom Lee-Devlin

This book is a broad history of the city, and why urbanisation continues to be an unstoppable force around the planet. Goldin and Devlin end up with a whole lot of recommendations to make cities better, starting with restricting cars – as spending time in any city that has tamed the car even a little bit makes you realise just how much better cities can be if cars don’t completely take them over. Their broad recommendations are:

- Overhaul urban design – by restricting cars, reintroducing mixed used neighbourhoods, improving housing affordability in the centre and expanding social housing so that communities are more socioeconomically integrated.

- Rebuild for the knowledge economy – accept that manufacturing jobs are never going to reappear at scale in rich countires (even if manufacturing returns, it will largely be automated). So cities need to increase high-skill employment opportunites, and bring in skilled workers by making the city a more liveable place. And educate their citizens better – by giving all children access to a good education, not just the rich children.

- Accelerate sustainable development – by helping cities in poorer countries avoid informal settlements lacking in basic services, and to avoid car-based sprawl. The planet cannot afford to increase the proportion of transport that happens in cars.

- Deliver locally, support nationally, coordinate globally – the authors have strong views on making sure decisions are made at sensible levels – using the principle of subsidiarity, which is that decisions should be made as locally as possible, rather than by a centralized level of government that is too far away from the affected community. They have a small caveat to that, suggesting that city wide governments (including the associated suburbs) work much better than multiple local governments that are uncoordinated.

While the authors used Sydney in several examples, both of good and bad city design, they are mostly writing for the US and the UK, so it is really interesting to read their prescriptions and realise how relevant they can be here in Australia. This is a great book that brings together a lot of thinking about cities and what makes them tick.

How the World made the West, a 4,000 year history, by Josephine Quinn

How the World made the West, a 4,000 year history, by Josephine Quinn

This was my favourite history book this year. Quinn wrote this book with the aim of refuting the common cultural view (represented, for example, here at the Ramsay Centre for Western Civilisation) that the only forerunners to our societies today worth studying are the ancient Greek and Roman societies. Quinn makes the strong case for the massive interrelationships between the ancient societies around the Mediterranean, as well as Persia, and even as far as India. Much of the innovation that is commonly credited to (especially) ancient Greece, such as democracy, actually comes from gradual innovation and sharing from all the societies around the area at the time.

I particularly enjoyed this because I was coincidentally in Cadiz, Spain, shortly after I read it. Cadiz was part of a network of trading routes around the Atlantic seaboard three thousands years ago, which also included Cornwall, Brittany and Galicia. The Phoenicians from Tyre (now Lebanon) joined them once they discovered the wealth of metals available in the area. around 1,000 BC. Archeological evience in Cadiz has trading goods from all over the mediterranean and the Atlantic coasts from three thousands years ago, with much evidence of sharing of technological improvements. A whole lot of really important innovations happened in that Atlantic seaboard/western Mediterranean area and were then exported to the eastern Mediterranean, including the ancient Greeks. Sadly there is also potential evidence of the introduction of slavery, to work all those metal mines that brought people to those shores in the first place.

This book is fascinating in its own right, I loved reading about the interrelationships between all the different societies and learning about the ones that haven’t really made it to our collective consciousness. But it is also very convincing in making its case that the tendency to credit the Greek and Roman “civilisations” with all the worthwhile technological and societal advancements that happened during up to and including medieval times is missing a huge swathe of the history of humankind in Europe and Asia.

And finally, one book of fiction that I particularly loved this year – I read a lot about cities this year, both in books and other media, and this novel seems particularly appropriate to round out this best of list.

The City and the City, by China Mieville

The City and the City, by China Mieville

I found this book via all the city builders and campaigners I’ve been following on social media, but unusually, it is fiction. It is the story of two cities in the same geographical space, separated, but yet intertwined. And it is a police procedural, which as the mystery unfolds slowly reveals more and more about how the two intertwined cities really work. In the hands of a good writer, the structure of a police procedural can provide just enough constraint for a great novel, and this one does that for me, with some philosophy thrown in.

I haven’t read much China Mieville (although I’ve often seem him recommended) and this book definitely makes me want to read more.

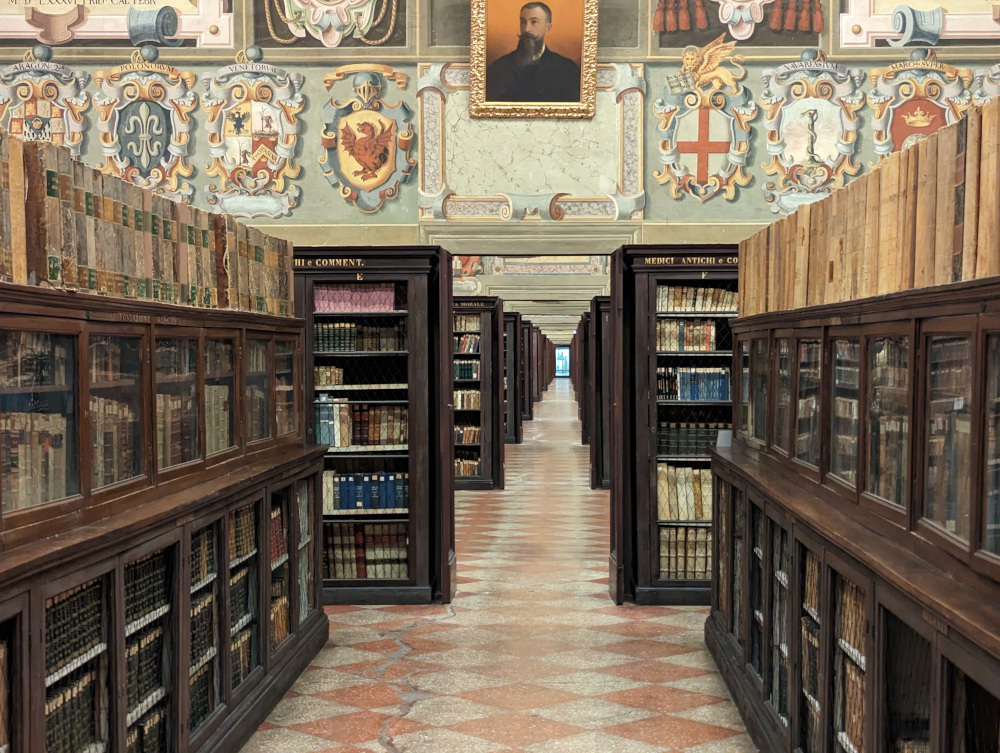

And as always, a bit of beauty to round out this post (book related, naturally). This picture is of the library of the Archiginnasio in Bologna, Italy. The Archiginnasio is the building where Bologna centralised its University in the 1600s. The University itself, though, is much older than that, it is the oldest university in Europe, with teaching having started in 1088.

Thanks for the reference to the Flybjerg book!

Thank you Jennifer for this list , always a year end favourite of mine to hear about what you have read . Happy new year !

Fascinating reading thanks for sharing.

Happy New Year Jennifer. Thanks for the books you listed- one is purchsed for my son’s birthday (How the World May the West) & I am going to find The City The City at the library!

I always enjoy your newsletter.

See you at choir in a few weeks.

Thanks for the recommendations! If you’re interested in city development you should also check out the Strong Towns movement. It explains some of our bad outcomes and suggests solutions. Their focus on long term liabilities is very actuarial. I presented their ideas at the recent NZ actuarial conference and it was well received. We should spread the word!