As has become tradition over a surprising number of years (this is the 15th!), every year I post a list of all the non fiction books I read the previous year. I do also read fiction, but posting all of that involves revealing some of the trashy things I’ve read, so I generally just post a couple of highlights. This year my theme has been cities; I’ve started following a bunch of city planners on social media and have been following their book recommendations.

Cities

Age of the City, why our future will be won or lost together, by Ian Goldin and Tom Lee-Devlin

Age of the City, why our future will be won or lost together, by Ian Goldin and Tom Lee-Devlin

This book is a broad history of the city, and why urbanisation continues to be an unstoppable force around the planet. Goldin and Devlin end up with a whole lot of recommendations to make cities better, starting with restricting cars – as spending time in any city that has tamed the car even a little bit makes you realise just how much better cities can be if cars don’t completely take them over. Their broad recommendations are:

- Overhaul urban design – by restricting cars, reintroducing mixed used neighbourhoods, improving housing affordability in the centre and expanding social housing so that communities are more socioeconomically integrated.

- Rebuild for the knowledge economy – accept that manufacturing jobs are never going to reappear at scale in rich countires (even if manufacturing returns, it will largely be automated). So cities need to increase high-skill employment opportunites, and bring in skilled workers by making the city a more liveable place. And educate their citizens better – by giving all children access to a good education, not just the rich children.

- Accelerate sustainable development – by helping cities in poorer countries avoid informal settlements lacking in basic services, and to avoid car-based sprawl. The planet cannot afford to increase the proportion of transport that happens in cars.

- Deliver locally, support nationally, coordinate globally – the authors have strong views on making sure decisions are made at sensible levels – using the principle of subsidiarity, which is that decisions should be made as locally as possible, rather than by a centralized level of government that is too far away from the affected community. They have a small caveat to that, suggesting that city wide governments (including the associated suburbs) work much better than multiple local governments that are uncoordinated.

While the authors used Sydney in several examples, both of good and bad city design, they are mostly writing for the US and the UK, so it is really interesting to read their prescriptions and realise how relevant they can be here in Australia. This is a great book that brings together a lot of thinking about cities and what makes them tick.

Carmageddon, how cars make life worse and what to do about it, by Daniel Knowles

Carmageddon, how cars make life worse and what to do about it, by Daniel Knowles

This book brought together many of the ideas that I’ve been finding in the last few years since I joined the board of Bicycle Network. There are many ways that cars make cities much worse for the people who live in them. Starting with taking up a ridiculous amount of space. For example, in Houston, US, there are 30 parking spaces for every car (many of which are legally required). And of course, pollution (noise and air) is massively increased by car traffic, and deaths by cars is one of the major causes of death around the world for people under 65.

Spending two weeks in Toulouse this year made me appreciate how nice a city can be when cars are rare. Toulouse has an inner city that has been largely reclaimed from cars, including banning cars from several former car bridges across the river Garonne, and reclaiming the main urban square from car parking so that it is full of cafes and people hanging out watching urban street performances.

As Knowles says

Cars are not just about how you get around. They are about what the city you live in looks like and what your daily life feels like. The car goes to the core of almost everything, dominating almost all public spaces to the detriment of pedestrians and cyclists.

But sadly, once you get too far down the road of building cities for cars, it is impossible to live in one without a car. Knowles has lived around the world, which makes this polemic against cars more interesting than the average rant from a western writer – he has much more understanding of the issues in poorer countries, and what could happen if the focus of policy makers is shifted so that incentives are in favour of the least damaging forms of transport (rather than the most damaging).

The City and the City, by China Mieville

The City and the City, by China Mieville

I found this book via all the city builders and campaigners I’ve been following on social media, but unusually, it is fiction. It is the story of two cities in the same geographical space, separated, but yet intertwined. And it is a police procedural, which as the mystery unfolds slowly reveals more and more about how the two intertwined cities really work. In the hands of a good writer, the structure of a police procedural can provide just enough constraint for a great novel, and this one does that for me, with some philosophy thrown in.

I haven’t read much China Mieville (although I’ve often seem him recommended) and this book definitely makes me want to read more.

The Business World

How Big Things Get Done: The Surprising Factors Behind Every Successful Project, from Home Renovations to Space Exploration, by Bent Flyvbjerg and Dan Gardner

How Big Things Get Done: The Surprising Factors Behind Every Successful Project, from Home Renovations to Space Exploration, by Bent Flyvbjerg and Dan Gardner

This was my favourite book this year. Flyvbjerg has made a career of analysing big projects, starting in Denmark with big construction projects, and then moving ever wider, both geographically and type of project. With a mixture of storytelling and didactic lessons, he and his coauthor Gardner use their experience and analysis of all these projects to take out a pithy set of lessons about how best to make big projects work as intended.

This book is full of insights, many of which I have bored friends, family and colleagues with this year. It is structure around the stories of good projects (the Bilbao Guggenheim) the bad (the Sydney Opera House), and the ugly (California High Speed Rail). But the real gold is in the 11 heuristics for better projects, that the book finishes with.

- Hire a masterbuilder – always start with someone with deep experience in a project very like the current project

- Get your team right – I think this lesson is deeply underrated. A team that has worked together on project after project in any field is always better than a team of superstars assembled for the first time.

- Ask Why – the purpose for any given project might not be the public one – the Guggenheim in Bilbao is a great example of this. The purpose was not an art gallery, it was a building to put Bilbao (a declining industrial town) on the map.

- Build with Lego – prototype as much as humanly possible before you start

- Think slow, act fast – this one seems obvious, but the world is littered with mistakes that seem obvious in retrospect that weren’t recognised in advance

- Take the outside view – find the class of projects that your project belongs to and learn from it, don’t think that your project is unique and special (this is a particular problem for the Olympics, and probably why they are some of the worse overrunning projects)

- Watch your downside – think really hard about all the risks and mitigate them, rather than just adding budget for them

- Say no and walk away – the most successful project managers don’t take on everything they are offered

- Make friends and keep them friendly – a big project has stakeholders everywhere, many of whom can massively disrupt a project if they are not happy. They are part of the job, not just a distraction

- Build climate mitigation into the project – this is both about understanding risks (which have increased with climate change) and doing your part not to make it worse

- Know that the biggest risk is you – hubris – thinking that you won’t make all the mistakes everyone else has made.

This book is a highly readable analysis by authors who really, deeply know their stuff – those lessons are much more impactful after reading the stories that go with them. Should be compulsory reading for anyone who involved with a big project.

The Art Thief, by Michael Finkel

The Art Thief, by Michael Finkel Billion Dollar Whale: The Man Who Fooled Wall Street, Hollywood, and the World by Bradley Hope, Tom Wright

Billion Dollar Whale: The Man Who Fooled Wall Street, Hollywood, and the World by Bradley Hope, Tom Wright

History and Travel

How the World made the West, a 4,000 year history, by Josephine Quinn

How the World made the West, a 4,000 year history, by Josephine Quinn

This was my favourite history book this year. Quinn wrote this book with the aim of refuting the common cultural view (represented, for example, here at the Ramsay Centre for Western Civilisation) that the only forerunners to our societies today worth studying are the ancient Greek and Roman societies. Quinn makes the strong case for the massive interrelationships between the ancient societies around the Mediterranean, as well as Persia, and even as far as India. Much of the innovation that is commonly credited to (especially) ancient Greece, such as democracy, actually comes from gradual innovation and sharing from all the societies around the area at the time.

I particularly enjoyed this because I was coincidentally in Cadiz, Spain, shortly after I read it. Cadiz was part of a network of trading routes around the Atlantic seaboard three thousands years ago, which also included Cornwall, Brittany and Galicia. The Phoenicians from Tyre (now Lebanon) joined them once they discovered the wealth of metals available in the area. around 1,000 BC. Archeological evience in Cadiz has trading goods from all over the mediterranean and the Atlantic coasts from three thousands years ago, with much evidence of sharing of technological improvements. A whole lot of really important innovations happened in that Atlantic seaboard/western Mediterranean area and were then exported to the eastern Mediterranean, including the ancient Greeks. Sadly there is also potential evidence of the introduction of slavery, to work all those metal mines that brought people to those shores in the first place.

This book is fascinating in its own right, I loved reading about the interrelationships between all the different societies and learning about the ones that haven’t really made it to our collective consciousness. But it is also very convincing in making its case that the tendency to credit the Greek and Roman “civilisations” with all the worthwhile technological and societal advancements that happened during up to and including medieval times is missing a huge swathe of the history of humankind in Europe and Asia.

Unfortunately, she was a Nymphomaniac, a history of Rome’s imperial women, by Joan Smith

Unfortunately, she was a Nymphomaniac, a history of Rome’s imperial women, by Joan Smith

Smith’s first book, Misogynies, is still on my bookshelf from my first flurry of reading feminist books. This book uses Smith’s background as a Latin scholar to make the case that historians are generally very good at scepticism about Roman sources and their agendas (who hated who, who was on which side, who wanted to trash a particular emperor’s reputation posthumously etc) except in the case of women. In the case of women, every description of a woman “provoking” violence or even murder by being too powerful, or suddenly becoming incredibly promiscuous tends to be believed. Smith’s first example is a British Museum caption aimed at schoolchildren:

“Nero’s mother and wives were powerful. Ancient writers said that Nero had them killed. Nero said his mother and first wife betrayed him. Who would you believe?”

Smith argues that this caption regurgitates the defense offered by pretty much every abuser who has killed a current or former wife – “she made me do it”. But in the case of roman history, the sensible scepticism for those kinds of justifications seems (still!) completely absent.

Sadly I’m not interested enough in roman history to really follow the twists and turns of all the emperors and their wives and daughters. It’s particularly confusing as women didn’t even get their own first names, just the feminine versions of their father’s name. Famously, interest in roman history is most common in men of a certain age. They’re probably the ones who should read this book, but won’t.

Merchant Kings, when Companies ruled the world 1600-1900, by Stephen R Brown

Merchant Kings, when Companies ruled the world 1600-1900, by Stephen R Brown

There’s always a fresh way to tell history, and this one is right up my alley. It is the story of six men who, by running a company which was the merchant arm of their countries’ foreign policy at the time, had enormous power over large swathes of our planet during their time in power. Starting with the Dutch East India Company and ending with Cecil Rhodes and hte British South Africa Company, it is a reminder of the enormous riches the European powers managed to extract from the rest of the world during their various times of peak power.

A good reminder, in times when many former colonies are demanding acknowledgement, and in some cases, reparations, of the enormous riches available to the ruthless commercial monopoly backed by a state’s military power. Often the riches accrued to the Europeans on the spot, but they rarely went back to anyone local.

Spain: the Trials and Triumphs of a modern European Country, by Michael Reid

Spain: the Trials and Triumphs of a modern European Country, by Michael Reid

With my third trip to Spain in three years this year, I realised it was time to update my understanding of the country. My brother had previously recommended Ghosts of Spain, a book about the Spanish Civil War’s echoes through to the modern day, but Spain is more than this.

It is a fascinating country, and so much more than any stereotype, whether it is the southern beaches covered with concrete, the Catalan separatists, or the deep catholicism that still exists in parts of the country. I find myself unable to summarise this book, but would really recommend it for anyone who would like a deeper understanding of an underrated country.

High Caucasus: A Mountain Quest in Russia’s Haunted Hinterland, by Tom Parfitt

High Caucasus: A Mountain Quest in Russia’s Haunted Hinterland, by Tom ParfittPolitics and public policy

The Forever War, America’s Unending Conflict with Itself, by Nick Bryant

The Forever War, America’s Unending Conflict with Itself, by Nick Bryant

Nick Bryant was formerly a BBC foreign correpondent (in the US among many other places), and now lives in Australia. This book came out in the middle of 2024, as the US Presidential campaign was hotting up, and I was failing to keep my promise to myself not to obsess about the US election. It was a good book to read on the topic, if I was only going to read one, as it makes the argument that the political distrust, violence and hatred that we see in the US are not a new phenomenon, and in fact have been there since the beginning. The Civil War of the 1860s was the peak, but there have been violence, divisiveness, hate and even massacres periodically thoughout the nearly 250 years of United States history.

In some ways that thought is quite depressing, but in other ways it makes it easier to understand the underbelly of US exceptionalism. A really interesting angle on the US past and present that I can imagine myself rereading during the Trump presidency.

Working for the Brand, how corporations and destroying free speech, by Josh Bornstein

Working for the Brand, how corporations and destroying free speech, by Josh Bornstein

Josh Bornstein is an Australian employment lawyer, who has spent a lot of time on cases where employees have been sacked for things they have said on social media. He points out how incredibly vague employment contracts and company social media policies such as “ensuring the company is not brought into disrepute”, “don’t use social media in a way which may compromise the reputation and integrity of the company”, “don’t engage in activities in their private life that could adversely affect the reputaiton and integrity of the company” and other similar clauses.

While on first glance, these seem quite reasonable, they leave companies and employees incredibly vulnerable to a pile-on, if an employee says something on social media that could be regarded as unacceptable by parts of the community (such as criticizing Anzac Day, advocating for gay marriage, or being homophobic), or employees do something in their private life that some would find unacceptable (such as having an affair). The words can be vague enough that they can be used to sack people in ways that were probably not intended when they were first drafted.

It is a thought provoking book. Ways in which employers expect and get control over employees in their private lives have been gradually increasing. Bornstein’s examples make it clear that the people who are caught by this control can be individuals doing things that in many contexts would seem quite innocuous, except that they have been unlucky enough to attract attention from powerful people or social media mobs.

Breaking the Boss Bias, how to get more women into leadership, by Catherine Fox

Breaking the Boss Bias, how to get more women into leadership, by Catherine Fox

Catherine Fox was, for many years, the author of Corporate Woman in the Australian Financial Review, a tiny corner of feminism in a newspaper that was often the complete opposite. During that time, and since, she has written many books looking at the experience of working women, using rigorous research and her experience of talking to senior leaders to make her arguments.

“Delusions of progress have protected the power status quo, and held women back. It’s time to focus on addressing the cause [rigid gender stereotypes and bias], not the symptoms, of the disadvantage keeping half the world’s population out of power.”

I always enjoy reading Fox’s books, and enjoyed this one, but sadly it did feel as if I was still reading the same book again. That’s completely consistent with Fox’s thesis, that the problem of gender equality hasn’t gone away, even if progress is being made (glacially slowly). But I didn’t find this one quite as compelling as Fox’s previous books.

Who’s afraid of Gender, by Judith Butler

Who’s afraid of Gender, by Judith Butler

Judith Butler is an American feminist academic and philosopher who is best known for their book Gender Trouble: Feminism and the subversion of identity. Their books are famously dense, but also famously insightful and influential on feminist and queer theory. So it was with some trepidation that I decided I really needed to read this one, given the worldwide attacks on trans people and their rights.

Judith Butler is the best person to help you understand trans inclusive feminism (as opposed to the exclusionary version) which is what I really wanted, as a feminist with two trans children.

Luckily, this book is much more readable for the non academic than Butler’s usual books. As well as reiterating their thoughts on gender in a way that is readable for the non academic, Butler also looks around the world at how authoritarian regimes are using gender as a pantomime villain to demonise struggles for equality. They also carefully examine the strong links between “anti-gender” campaigns and xenophobic panics about migration and critical race theory. Butler makes the case for coalition building and the need for those campaigning for equality in different dimensions to work across those dimensions.

Reading this book has made me much more aware of the different dimensions of equality – as a feminist, sometimes I forget to think about inequality in dimensions other than gender. It’s a good reminder that privilege exists in many forms, and those of us who have it, should try and use it to help others.

How to Lose Friends and Influence White People, by Antoinette Lattouf

How to Lose Friends and Influence White People, by Antoinette Lattouf

Antoinette Lattouf is an Australian journalist, and cofounder of Media Diversity Australia. In 2023, she was sacked by the ABC three days into a five day contract, for posting a report from Human Rights Watch on social media, alleging that Israel was using starvation as a weapon of war. While I had heard of Lattouf previously, I was interested enough to buy this book, which she wrote in 2022, talking from experience about how to make a difference when championing change and racial equality.

When you look at media in Australia, and compare the faces you see on screen with those you see in the street, there is a real cultural and racial disparity. I’m not the person who can make a difference in media, but of course this same disparity exists in the corporate world too, where I can have some influence. I used to think that the structural impediments to equality at senior level for women would be the same as those for people from other marginalised backgrounds, but that isn’t always true. And reading this book provided some more data points to help me understand that, and think about what I might be able to influence.

Fiction

Some Desperate Glory, by Emily Tesh

Some Desperate Glory, by Emily Tesh

This book won the Hugo this year, it’s a fascinating novel of alternate histories and authoritarianism, a space opera set in a future where humans are part of a much bigger universe, and some are happier about that than others. Saying much more about it would give away some of the great plot twists, that made it excellent, so if space opera is your thing, go and read this one!

An astonishingly good book for a first novel.

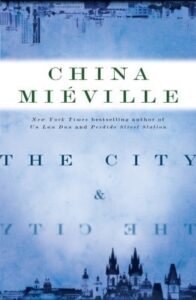

And as always, a bit of beauty to round out this post (book related, naturally). This picture is of the library of the Archiginnasio in Bologna, Italy. The Archiginnasio is the building where Bologna centralised its University in the 1600s. The University itself, though, is much older than that, it is the oldest university in Europe, with teaching having started in 1088.