Every year the ABS analyses the mortality statistics for Australia. And every couple of years, I have a look at them for this blog.

Every year the ABS analyses the mortality statistics for Australia. And every couple of years, I have a look at them for this blog.

This year, the news from other countries has not been great. In the UK, as The Actuary reports, life expectancy has ground to a halt, with no improvements over the last three years. The Actuary quotes the International Longevity Centre – UK (ILC-UK) said the latest findings should be “taken with a pinch of salt”, and highlighted how incomes impact life expectancy.

What is clear from our research is that the gap in life expectancy between the rich and poor is worsening over time. The reasons behind these disparities are complex, but it is utterly unacceptable to witness a growing health divide in 21st century Britain.

So I was interested to see what has happened in Australia. Professionally, I’m most interested in mortality during the peak period of insurance needs – between ages 30 and 64, when people are working, and supporting their families with their income, so have the greatest need to insure against premature death. And in Australia, at least, the news continues to be good. Death rates have dropped in pretty much age group for men and women for working people.

So I was interested to see what has happened in Australia. Professionally, I’m most interested in mortality during the peak period of insurance needs – between ages 30 and 64, when people are working, and supporting their families with their income, so have the greatest need to insure against premature death. And in Australia, at least, the news continues to be good. Death rates have dropped in pretty much age group for men and women for working people.

Interestingly, particularly for males, there was a little bit of an uptick in mortality rates in 2014 and 2015, and the female mortality improvement slowed down in the same years. But now we in Australia seem to be back to improving mortality rates.

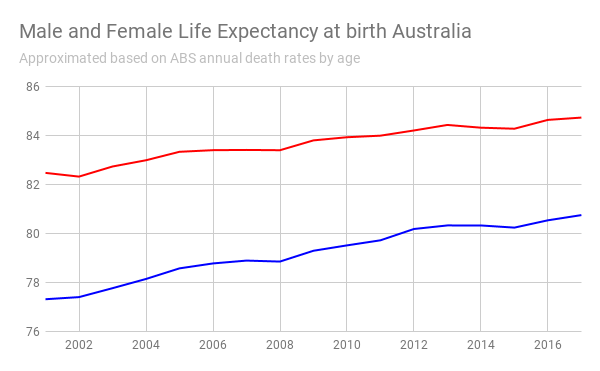

For the population as a whole, the trend appears quite similar.  I have calculated an estimate of life expectancy based on the ABS aged based death rates, and the graph shows gradual improvement. There was a bit of a flattening of improvement in 2014 and 2015 for both men and women, and then in 2017 the upward trend continued.

I have calculated an estimate of life expectancy based on the ABS aged based death rates, and the graph shows gradual improvement. There was a bit of a flattening of improvement in 2014 and 2015 for both men and women, and then in 2017 the upward trend continued.

This isn’t something we should take for granted. In the US, life expectancy has declined for two years in a row, according to the Centre for Disease Control, most likely because of the opioid epidemic, and associated diseases including liver diseases and suicides.

Depending on how you measure it, Australia is generally in the top 5 countries in the world for life expectancy. And we continue to improve.

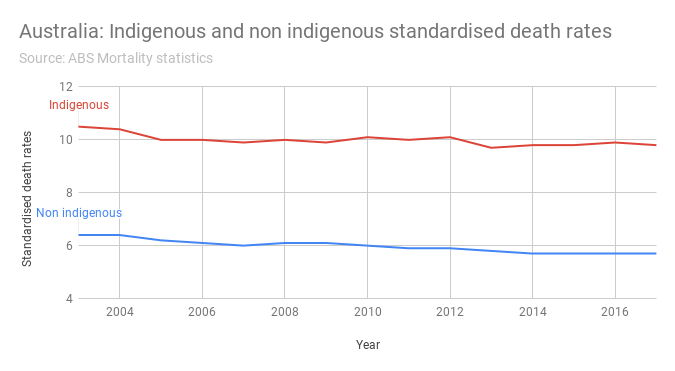

But it isn’t all good news. As I’ve previously noted, Australia shamefully has an enormous gap in life outcomes between indigenous and non indigenous people. And over the period that of these statistics, while both indigenous and non indigenous mortality has improved, the gap has widened, with standardised indigenous death rates going from 164% of non indigenous rates to 172% of non indigenous rates between 2003 and 2017.

But it isn’t all good news. As I’ve previously noted, Australia shamefully has an enormous gap in life outcomes between indigenous and non indigenous people. And over the period that of these statistics, while both indigenous and non indigenous mortality has improved, the gap has widened, with standardised indigenous death rates going from 164% of non indigenous rates to 172% of non indigenous rates between 2003 and 2017.

The most recent life expectancy calculated by the ABS for the period 2010-2012 shows that the average gap in life expectancy between aboriginal and non aboriginal people was 10 years, with life expectancy at birth for indigenous men being 69 years compared with nearly 80 years for non indigenous men (the numbers were 73.7 and 83.1 for women). That puts indigenous Australians around the same mortality rates as people in Egypt or Bangladesh.The ABS highlighted that:

For males, the largest differences were in the 35-39 year and 40-44 year age groups, where mortality rates for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males were over four times higher than rates for non-Indigenous males.

For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander females, the largest differences were in the 25-29 year to 35-39 year age groups, where mortality rates were around five times higher than rates for non-Indigenous females.

So we may be the lucky country, but we certainly aren’t lucky for everyone.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Glossary

Standardised death rates as calculated by the ABS: Deaths per 1,000 standard population. Standardised death rates use the age distribution of total persons in the Australian population at 30 June 2001 as the standard population.

Life expectancy at birth: Calculated as the average age a baby born today would live to if the average death rates at each age of his or her life was the risk of death at that age.