The shocking murder of a woman and her three children by her ex-husband (and the children’s father) in Queensland this week has led to a lot of discussion of the statistics of family violence. The statistic I want to look at today is the deaths of children. The Drum on the ABC talked about this on Wednesday.

One child per fortnight. One child. Per fortnight. By a parent. Killed by a parent. Per fortnight. In Australia. https://t.co/n59L3cIlDo

— Natasha Mitchell🎧🎙 (@natashamitchell) February 21, 2020

According to journalist Jess Hill (author of the excellent See what you made me do), nearly one child a fortnight is killed in family violence in Australia. But the government does not track this statistic.

The Australian Institute of Family Studies has pulled together a list of all the research into deaths of children from abuse and neglect. Everything in it is sobering.

But the statistic of children killed by filicide (killed by a parent or step-parent) comes from a study that was conducted by the Monash-Deakin Universities Filicide Research Hub (MDFRH) in partnership with the Australian Institute of Criminology (AIC). You can read a summary here, and the full study (pdf) here.

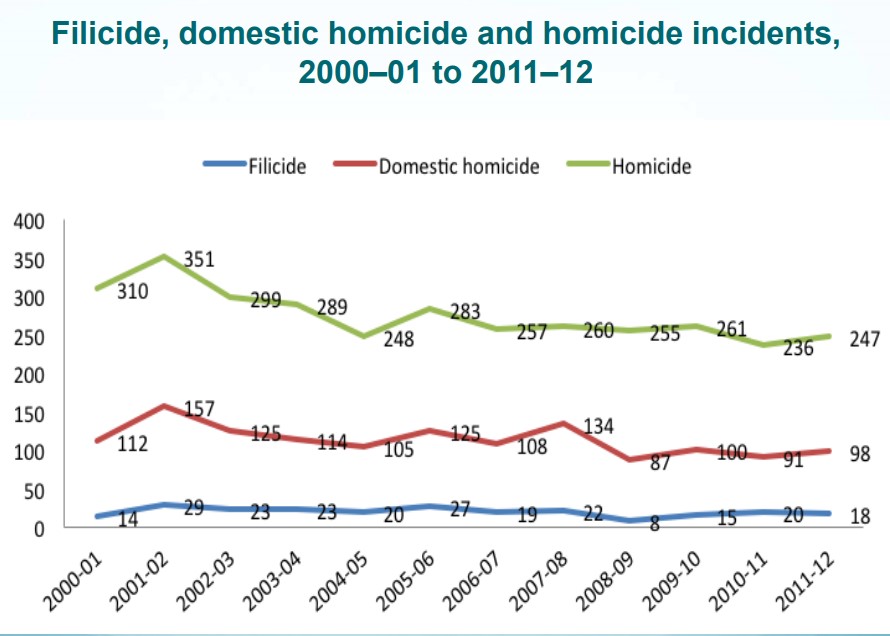

For a start, it confirms the statistic. During the study period between 2000–01 and 2011–12, there were 284 victims of filicide, which is just under 25.8 per year, or one per fortnight. That’s 63% of child homicide victims during the period.

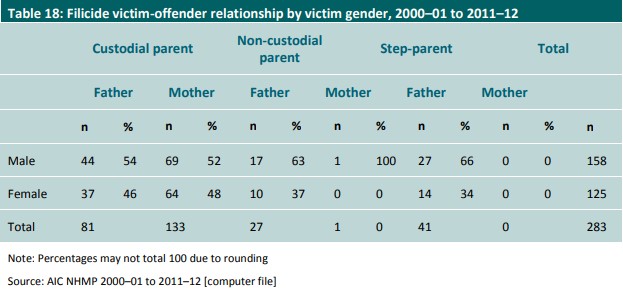

The most horrific stories (such as the one which sparked this blogpost for me) are committed by men. But I was quite confronted to discover that about half of filicides are committed by mothers.

The motives between female and male offenders are generally different. According to the study:

Five categories were established:

- altruistic filicide (to relieve the child’s suffering and often involving the suicide of the offender);

- acutely psychotic filicide;

- unwanted child filicide;

- accidental filicide; and

- spouse revenge filicide (Resnick 1969).

Altruistic and acutely psychotic filicide events were predominantly associated with female offenders, while accidental and spouse revenge filicides were predominantly associated with male offenders.

So what can be done? As the study points out, while one filicide a fortnight is a horrific number, it is still small enough that distilling commonality between each event to work out how to prevent filicides is not obvious. The study shows the major risk factors:

Criminal history – especially of fathers and stepfathers – has emerged as a major new factor in filicide risk. Major risk factors have now been established as a “constellation” of reasons – mental illness (especially in young mothers), domestic violence inflicted by fathers and stepfathers, parental separation, past child abuse, substance abuse and past criminal history.

This leads to the major recommendation arising from the study, says Emeritus Professor Thea Brown, one of the lead researchers.

Psychiatric services are in general not looking at people they see as parents who might potentially harm their children. The full extent of the dangers of a condition like depression are still not recognised. A person suffering from depression can harm themselves and harm others, but it’s generally seen as a minor mental health issue. Our submission will stress that mental health services aren’t identifying the right people in terms of potential filicide.

There has to be more communication about filicide with everyone involved in mental health. So, for example, when a woman goes to see her GP and says she’s depressed, the GP knows to ask about domestic violence and other parts of her history so as to see whether she’s at risk. The GP should immediately be asking if she’s responsible for young children, whether she wants to hurt herself or others, and all about her partner and his history. People in these situations tend to be treated as individuals, and not the parents of young children.

I would add to that a plea for data. It took me several attempts to find this study, as it isn’t referenced in any official statistics. It There is no official record of deaths from family violence – children, women or men. As this article points out, Australia has no Violence Against Women & Children Toll. It has no organisation dedicated to the detailed reporting of femicide, family violence and the killing of children. As the article points out, this is another example of the gendered collection of data, where data is collected in ways that prioritise male experience (in non obvious ways). There is government data on the road toll and workplace deaths and injuries. Both of these types of deaths are disproportionately male (although that statistic is rarely shown in summaries). But the deaths of children at the hands of their parents are not tracked by any official body. And as a result, the statistic that one child dies at the hand of a parent or step parent every fortnight is a shocking surprise.

If there was a government agency charged with tracking statistics on family violence and particularly homicides, it would make it more likely that action would be taken to reduce this terrible number so that not so many children would die.

How tragic

Jennifer, this is a topic I actually know something of.

I once was assigned to keep track of a region of Child Protection Victoria databases (we had about 5 or 6 which never reconciled). I had trained in social welfare, but also my economic thesis had about misunderstanding KPIs, meten is weten. Rather, gelang voor wat gemeten (giving importance to what measured) instead of meten wat belangrijk (measuring what is important). I had also studied Biology which turned out to be helpful (habeas corpus – produce the body).

There are various definitions of Family Violence: particularly between Criminal courts, Childrens Courts and Family courts: let alone within Police practices, social work and medical fraternity. I stressed that if anyone says something like last year there were 68 women killed by current or former partners, they are bound to be making the figure up or ignorant of such things. For instance, Police investigation take months, state Coroners take months if not years to reach conclusions, and criminal cases always take years. The figures for any time period will go up and down as the various authorities complete their work: most up. Although, names can be distracted too. So broad professionally guided estimates ought be more trusted. They are acknowledging the uncertainty.

I show the students had to integrate crime states, epidemiological studies, State Child Death Inquiries, Commonwealth Crime Intelligence Agency, Institute of Health and Welfare, academic studies, media reports, case experince, etc. I also encourage them to read up Australia’s anthropologist, botanical illustrator, activist for Aboriginal rights Olive Pink to appreciate that there is some information professional choose not to gather as it serves no good.

But before I have them doubting everything, eg, the Monash-Deakin Universities Filicide Research cited is quite flawed – But for good motives. I at less have the students appreciate that in Victoria in the 1970s there were 25-30 women and children wantonly killed each year, and it is now 10-15 each year; or about 15 families not experiencing untold grief each year. Never tell me it should be none as I know enough graves where frail bodies are buried.

Most of this reduction is due to advances in medical technology, with law reform, change practices of Police, Child Protection, development of support services helped a bit. I add that NSWs spends percapita twice as much as Victoria on Child Protection services with no discernible difference in child deaths. But we can readily reduce the incidence of women and children being killed by half over the next decade and are well on the way to doing so.

That part though is another subject.