Can contact tracing reduce or remove the need for physical distancing? Contact tracing, when done quickly and effectively, removes some transmission, but not all of it. And the more cases there are, particularly in an environment without much physical distancing, the more the chances of a superspreader that will cause an outbreak to take off in a community (as it has in Victoria).

New South Wales has had daily community transmission cases in the teens since mid July – this article in the SMH yesterday points out that over the past two weeks, we’ve had over 150 cases.

Since March, everything I’ve read about how to keep the pandemic under control has been about testing and contact tracing. And NSW, like Victoria before us, has been doing just that. There have been an average of nearly 20,000 tests a day during the last week, and every day, NSW Health publishes a long list of places where, if you’ve been there on certain dates, you need to get tested whether or not you have symptoms. But if people continue to see each other (that same article points out that most people have 9-10 contacts to trace), is it possible for testing and contact tracing alone to keep the virus under control?

According to this Australian evidence review:

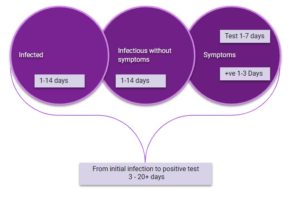

The median incubation period for COVID-19 is 4.9 to 7 days, with a range of 1 to 14 days. Most people who are infected and develop symptoms will develop symptoms within 14 days of infection…

…After initial infection with SARS-CoV-2, it takes a number of days for viral replication to produce enough genetic material to be detected by PCR. This occurs roughly 2-3 days before symptoms become apparent.

The hard thing about this, is that each step in in the process has a wide range of outcomes. The development of infectiousness can take 1-14 days, the development of symptoms can is also variable (although I don’t have a source for this one) and then the number of people infected by an infected person depends both on their level of infectiousness (which is quite variable) and the number of people that they come into the right kind of contact with.

So I’ve built a little illustration of how it might play out with two different people. It makes it clear that contact tracing reduces the time that people are infectious without being aware (particularly those who never get symptoms) but it doesn’t stop oblivious infectiousness entirely. So while a superspreader would hopefully be stopped earlier, they wouldn’t be stopped from some degree of superspreading. If the middle of the distribution holds, then eventually, this outbreak will die down. But if there are more than one or two people who stay infectious without symptoms for some time, and see a lot of people in ways they could pass the virus on, then suddenly the outbreak will be impossible to contain without distancing.

The diagram shows a reasonable range of timing from infection to developing symptoms, based on the research I linked to above. And the table shows a couple of examples – Alice and Bob – of the progression from infection to infectiousness to contact tracing.

Alice’s Covid19 progresses reasonably quickly, and she is not seeing that many people. She also gets tested almost as soon as her symptoms start to show and completely self isolates at that point. So there are 6 people who she might have infected before she was tested. And there are another four that the contact tracers will contact, as it isn’t clear when she was infected.

Bob, on the other hand, is infectious for quite a while before his symptoms start to show up. And he takes a few days to realise he should get tested. He cuts back on seeing people at that point, but not completely. It also takes an extra day for him to get his test results, so the contact tracing doesn’t start until day 14. For Bob, there are 30 people who he might have infected, and another four that the contact tracers should talk to.

There are two advantages of the contact tracing, compared with just testing and self isolating.

- The first is is that the stage when people will start isolating is earlier in this journey. Alice’s contacts will be contacted 8 days after she became infectious. While the people she infected on her first infectious day might be showing symptoms and be tested anyway, the others she infected later will then start isolating and being tested earlier, and so won’t infect as many people. Her average contact will be contacted 5 days after infection. Bob’s journey isn’t as quick, but even though the contact tracing doesn’t start until 13 days after he was infectious, he was still infecting people 4 days before contact tracing starts. Bob’s contacts will be contacted on average 8 days after infection. And while both of those delays allow infections to happen, they are both quicker than the point where Alice (7 days) and Bob (11 days) self isolated after their own infections.

- The second advantage is that around half of all infected people show few or no symptoms. While most experts think aren’t as infectious without symptoms, they can spread the virus. So those people wouldn’t get tested at all without contact tracing. Contact tracing will cause that chain to start again for each new infection even those if new people have no symptoms.

But this example shows that testing and contact tracing, by itself, doesn’t stop the spread. It does slow it down, both by finding people who are infectious faster, and also finding people without symptoms. This process only works well, though, if most people are like Alice. They aren’t seeing many people even before they are infected and they self-isolate and get tested as soon as they have symptoms. If we have someone like Bob, who is infected for a long time before his symptoms show up, and is seeing a lot of people each day, or someone even more infectious and gregarious than Bob, then we can still have a fast spreading outbreak, even if their contacts are traced perfectly.

It is also much harder for it to work if there are too many positive cases. While in theory it can be scaled up as long as you have enough people to do the contacting, the more people are testing positive, the more likely it is for the contact tracing to take longer than the day or two I have shown in my example, and if it takes too long, it doesn’t make enough of a difference.

So contact tracing (with readily available testing) is a crucial part of the fight against the virus, but it is hard for it to be enough without some degree of physical distancing if cases increase too much.

Links

This article in the British Medical Journal talks about decision making under uncertainty – certainly true of any Covid19 related decision being made right now:

As each country’s covid-19 experience shifts from an acute national disaster to a chronic policy crisis, we all—clinicians, scientists, policymakers, and citizens—need to move on from imagining that the uncertainties can be resolved. They may never be.

This is because covid-19 is, par excellence, a complex problem in a complex system. Complex systems are, by definition, made up of multiple interacting components. Such systems are open (their boundaries are fluid and hard to define), dynamically evolving (elements in the system feed back, positively or negatively, on other elements), unpredictable (a fixed input to the system does not have a fixed output) and self-organising (the system responds adaptively to interventions).

Managing uncertainty in a pandemic: five simple rules

- Most data will be flawed or incomplete. Be honest and transparent about this.

- For some questions, certainty may never be reached. Consider carefully whether to wait for definitive evidence or act on the evidence you have.

- Make sense of complex situations by acknowledging the complexity, admitting ignorance, exploring paradoxes and reflecting collectively.

- Different people (and different stakeholder groups) interpret data differently. Deliberation among stakeholders may generate multifaceted solutions.

- Pragmatic interventions, carefully observed and compared in real-world settings, can generate useful data to complement the findings of controlled trials and other forms of evidence.

And here’s a relink to a WHO epidemiologist from March saying all of that in simpler, and blunter language.

Life Glimpses

I’m signed up for the Actuaries Institute Virtual summit – normally over three days, it is now over a four week period with a few sessions each day. And today as part of my registration fee I received a package with a coaster for my cup of tea, a packet of mints, and some M&Ms! A very nice touch I thought, but I’m not sure if the M&Ms will last to the beginning of the summit (next Tuesday), let alone to the end. I can resist the mints for a bit longer. I’ve put them and the coaster in my zoom room to get me into the spirit of the conference.

And, in a small plug, one of the Plenary sessions at the Summit is this one, where I’ll be interviewing Professor Peter Doherty – Nobel prize winner and all around Australian national treasure. As a virus expert, he’ll have a lot to say about Covid 19 – how it works, the search for the vaccine and the amazing work the Doherty Institute is doing. But he’s also written a lot about science, and scientists, and how average citizens can inform themselves about what is really going on in his book The Knowledge Wars, and has some great insights on climate change. So come along if you are registered.

Bit of Beauty

This group of workshops that I can see from the north shore has always seemed to me like a tiny bit of Scandinavia in Balmain. I looked them up – they were originally for steamship repair and now house various creative and other small businesses. The lovely colours always seem to brighten the view.

Thanks for the “bit of Beauty” it always helps. The Covid-19 is reigning in Israel, finally they have

appointed one person who will be in sole charge as regards the virus. We will see,

Today I understood your Reflections much better, maybe there is still some hope for me.

Will there be a video of you interviewing Prof. Doherty, it should be interesting

It is hot here, height of summer

Love

Marta

I’ll be very disappointed if the contact tracer wasn’t Eve.

Jennifer, I like your example (with or without eavesdropping Eve). It illustrates the value of taking steps to reduce Alice and Bob’s (and Clare’s, etc) potential contacts, so that the contact tracing is a more manageable task. So masks and distancing very much have their part to play.

What’s missing from the picture is the quality of knowledge about the contact. That is, if one of Alice’s contacts is unknown to her (someone on the train or at the gym, say), there’s an extra delay while that person is made aware that the train/gym/whatever was a potential source of exposure. So signing in (with your real details) and/or effective use of the Covid Safe app is a major contributor to success in this fight. All the more so as we open up further and the number of contacts with strangers increases.

It’s encouraging, therefore, that NSW Health has been assisted by the app — and equally disturbing that Victoria is reported to have suspended its use for a period, albeit that it has limited value in lock-down.

Hi Jennifer, I had another look at the covid clusters we’ve had in Sydney. If you draw the chain from Crossroads to Thai Rock Wetherill Park to Thai Rock Potts Point to the Apollo, there are now just over 200 cases in this chain. While without contact tracing the number would undoubtedly have been higher, I struggle to see how it will stop the chains of transmission unless we start also isolating “contacts of contacts” given the timeframes involved. This is how SA are approaching their contact tracing and are putting a “double ring” around their school outbreak. Cheers, Karen

One interesting article I read https://www.crikey.com.au/2020/08/05/covid-19-testing-results/ points out that one of the uncertainties can be reduced by making the testing more efficient. It suggests paying pathology lab on a sliding scale $500 for a twenty-four hour turn around, almost nothing for three days, and the lab paying the government for time periods longer than three days.

The two people I know who have been tested have sen varied results — one had results back within twelve hours (Dee Why Respitory Clinic), and three days (RNSH).

Yes, a faster turn-around would improve things. I understand (but haven’t checked) that very slow turn-around is one of the issues in the US. (By the way, I know two people who’ve had tests at RNSH (a total of three tests) and I’m pretty sure that they got their results the next day, albeit perhaps not within 24 hours.)

And incentives would presumably lower the average time for test responses.

But let’s turbo-charge this. Of course, an instant-response test would be a game-changer, assuming that it was cheap enough to be widely used – e.g. for admittance on a flight and into a country. But what if there was a test that had a 15-minute turn-around time? Or one hour? Or two hours?

What’s the cut-off point for different environments? You couldn’t make a prospective supermarket customer wait two hours to be let in, but you might still want to apply it for flights and borders, thus adding a significant time impost.

Seems like the sort of question to toss around in a suitably social-distanced environment with a glass of fine wine!