Today I’m looking in depth at singing – how risky is it, and how does it compare with other activities? It seems to be slightly more risky than speaking at the same volume, but a much more important question is how well ventilated the space is, whether you are speaking or singing.

The NSW Health Advice says

There have been several clusters of COVID-19 in New South Wales in recent weeks, including a cluster linked to a church choir and attendance at a variety of activities related to a funeral. Singing in groups (whether by choirs or by congregants) or chanting is a particularly high risk activity and must not take place at this time, irrespective of whether singers or chanters are wearing masks. The only COVID-Safe singing that is permitted is a solo singer distanced at least five metres away from other people and not directly above the audience.

Without looking at these individual events referenced in the advice (which I couldn’t find in the contact tracing information easily, perhaps they are home or home linked events) I thought it was worth taking a look at a couple of studies of the risks of singing compared with talking, and breathing (and coughing).

A group at the University of Bristol analysed aerosol generation from a range of activities:

Here, we measure aerosols from singing, speaking and breathing in a zero-background environment, allowing unequivocal attribution of aerosol production to specific

vocalisations.

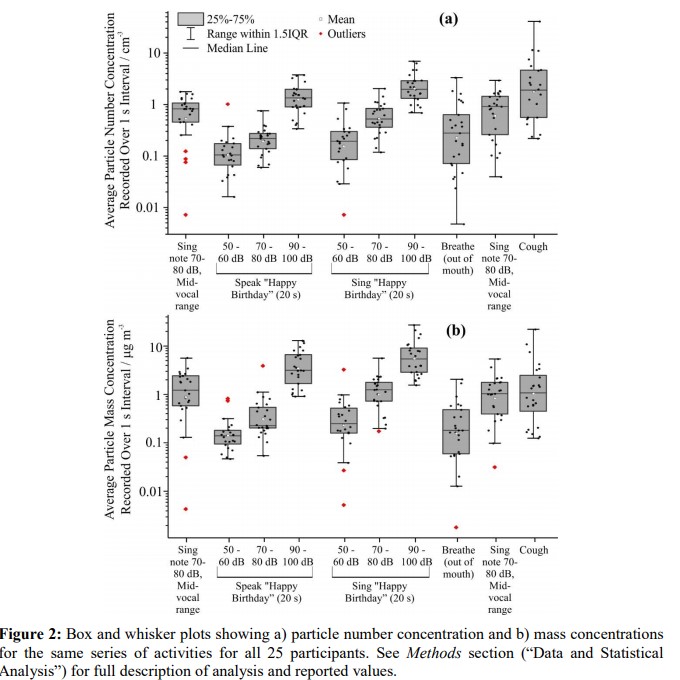

The diagram shows that there was some difference, between the level of aerosol production between singing loudly and speaking loudly but the difference was much less than the variability between people, even with breathing without any speaking or singing. Coughing, not surprisingly, is by far the riskiest activity, but even there there is a big range between individuals.

This study demonstrates that the assessment of risk associated with the spread of SARS211 CoV-2 in large groups due to respirable particles from speaking and singing should consider the number and mass concentrations of particles generated by these activities. The statistically significant, yet relatively modest differences detected between the type of vocalisation at the loudest volume studied, are eclipsed by the effects of volume on aerosol production, which varies by more than an order of magnitude from the quietest to loudest volume studied, whether speaking or singing. By contrast, the number of particles produced by breathing covers a wide range (spanning from quiet to loud volume speaking and singing) but has a size distribution shifted to smaller particle sizes, in principle mitigating some of the potential risk associated with the wider emission range. Based on the differences observed between vocalisation and breathing and given that it is likely that there will be many more audience members than performers, singers may not be responsible for the greatest production of aerosol during a performance, and for indoor events measures to ensure adequate ventilation may be more important than restricting a specific activity.

This study, from UNSW in Australia, comes up with much the same conclusions by comparing the sung notes in a scale with spoken numbers.

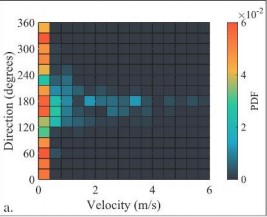

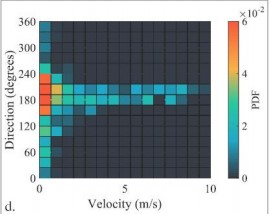

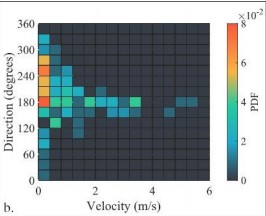

The results of detailed particle tracking (in supplementary video) reveals that the maximum velocity of droplets expelled, specifically for certain syllables such as ‘do’, ‘fa’ and ‘ti’, is approx. 6 m/s, which is similar to the velocities reported for speaking.

The distribution of the velocity of droplets from singing a full major scale appears to be slower than from counting from 1 to 10. I’ve shown both diagrams here. But the riskiest sung note is the note “fa”, which appears to be as bad as counting from 1 to 10.

The two studies appear to overall suggest that some singing is slightly riskier than talking. But while one of the two studies suggests statistical significance, it is only when the singing is at its loudest.

At the same time, analysis of location suggests much bigger differences.

Outdoors is much less risky than indoors – this study (not peer reviewed) from Japan suggests that there is almost 20 times more chance of being infected by someone indoors than outdoors:

The number of secondary cases generated by each primary case was calculated using contact tracing data. Results: Of the 110 cases examined, 27 (24.6%) were primary cases who generated secondary cases. The odds that a primary case transmitted COVID-19 in a closed environment was 18.7 times greater compared to an open-air environment (95% confidence interval [CI]: 6.0, 57.9). Conclusions: It is plausible that closed environments contribute to secondary transmission of COVID-19 and promote superspreading events.

That’s very consistent with the analysis I did of the NSW health data, where, based on the information provided in the weekly reports, there was only one set of transmissions that could have taken place outdoors (the soccer practice associated with one of the clusters) and even then that was more likely to have been indoor transmission than outdoors:

On interview with the case’s family it was identified that he attended mini-soccer training on 22 July while infectious but did not attend the game on 25 July. Between 25 July and 1 August, the case’s father, two of his teammates and a parent of each of these children who attended both the training and the game also tested positive. No cases have been identified in parents or children in the opposing team on Saturday 25 July. The public health investigation identified multiple opportunities for transmission including while car-pooling to training, at training or through close contact within the home.

Overall, singing loudly, particularly if you have strong consonants, seems to be slightly risker than talking at the same volume. But the location and ventilation of that location is a much bigger issue, reinforcing that whether you are singing or speaking, if you have any worry about community transmission, you should be doing so outdoors. As several of my choir contacts have pointed out to me, football chanting has not been mentioned anywhere in the local health guidance (and I’ve certainly seen pre and post game chanting at amateur games in local parks). That’s probably because, just like singing, it isn’t that risky if it happens outside with some distance between people.

Link

This very interesting article on Bloomberg from economist Tyler Cowen talks about the frequency of individually sensible risk based decisions being poor ones for society as a whole.

The more time passes, the more I wonder if I have, in fact, contracted an asymptomatic version of Covid. The chance of that was quite small in February, but as each month passes it becomes modestly more likely. That realization could easily nudge many people into taking just a bit more risk.

One of the worst things about not controlling the virus early is that it has created a class of citizens who are deciding to adapt to Covid-19 rather than avoid it. The way forward is through better coordinated public policy — including testing and tracing, prevention measures, and speedy health-care responses — rather than labeling individual Americans as stupid or misguided.

At the end of that article, Cowen talks about the importance of coordinating public policy, and communicating clearly. This article on managing quarantine builds on that to talk about the importance of clear communication and being realistic about human behaviour.

When we hear of people who have allegedly escaped from mandatory quarantine — whether that’s from hotels in Perth, Toowoomba, Sydney or Auckland — it’s easy to ask: “What were they thinking? Why didn’t they just follow the rules?”.

But our recent review shows people are less likely to follow public health advice if they misunderstand, or have negative attitudes towards it.

Social norms play an important role. If people believe there is a collective commitment to protect the community from further spread of infection, they are more likely to respect the public health measure. An individual’s participation can be conditional on whether they think others are also contributing.

Life Glimpses

I’ve been away in the South Coast of NSW with some friends for a few days since my last blog post. We were at one of the few beaches that didn’t burn over Christmas/New Year, although the part that didn’t burn was only the village itself – bush north, south and west all burned. It was sobering, 9/10 months later to see just how scarred the bush still is – and made you realise just how much hotter and more intense the fires had been than a “normal” fire (even those I’ve seen in the past that have destroyed houses). We managed to get to a kayaking place we’ve been to a few times before. It was lovely to see that they were still in business, given they basically missed their main season over summer, and then been shut down for Covid19 over Easter when the whole south coast had been hoping for a replacement season.

All the little towns up and down the coast were humming, which was both great to see for the sake of the businesses, and a little bit scary given the possible low levels of virus that still might be somewhere in the community in NSW – a lot of spreading opportunities over the school holidays.

Bit of beauty

Geekinsydney managed to capture this pelican from his kayak as the pelican took flight.

Thanks, Jennifer. I’m based in Switzerland so I’m bracing myself for a socially distanced winter. As you say, it’s important to communicate clearly on the benefits and get everybody on board.

I think the thing I miss the most is live music. I guess I’ll have to wait till summer (openair concerts) for that, based on your analysis.

The Swiss Police have a campaign #BliibDraa (swiss German for “Stay on it”) to encourage people to stick to the measures, stay home, hang in there: https://www.stadt-zuerich.ch/gud/de/index/gesundheitsversorgung/public-health/coronavirus-sars-cov-2/BliibDraa.html

P.S.: I love your blogs.

Glad you love the blogs Alicia, thanks.

Jennifer

I am guessing that comparing one person singing to one person speaking is not the real question. You don’t often get a whole choir of people speaking loudly, together and continuously for an hour or two – but singing: it happens all the time. That is where the risk is.

Brian

Good point Brian, and one which I haven’t seen in any of the analysis, interestingly. At my choir rehearsals, though, I wouldn’t expect it is that different from a group of 30 people milling around chatting for an hour or two – we learn different parts at a time (tenors, etc) with everyone else listening to them, and then do it all together. But if it was a concert, then that probably would be a bit riskier.

What a photo. How lucky to be at the right place ready to snap.