Are the Doherty Institute assumptions about vaccine effectiveness optimistic? And does it matter? Yes and yes. So we should monitor the spread of Covid19 closely as vaccination rates increase, and use 70% and 80% adult vaccination rates as guides, rather than stick to then as rigid rules to decide how to ease restrictions across Australia.

A reminder that the Doherty Institute report makes it clear that to control the Delta variant, ongoing public health and social measures such as contact tracing, isolating, and restraints on social mixing (compared with pre virus days) are needed no matter what vaccination rate is achieved, so a gradual guided relaxation of measures is what is recommended anyway.

In my last post, I commented that the Doherty Institute’s assumptions on the effectiveness of vaccines, particularly against the spread of disease, looked a bit optimistic compared with other world estimates. So I’ve had a look at whether those assumptions make a difference to the outcome. If you take the more conservative view of the UK modelling team, the Reff reduces by around 0.5 less than the Doherty institute assumes. That would mean the difference between a hard or a medium level lockdown in an outbreak (Victoria 2020) vs NSW July 2021). Or vaccination rates would have to go up by around another 10% before reducing the spread as much as the 80% of the adult population modelled.

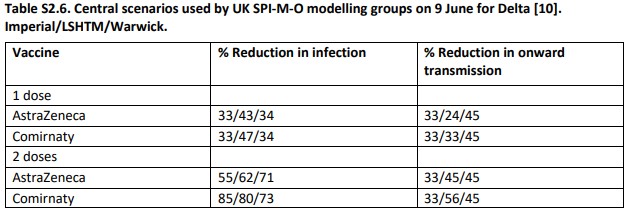

The table below shows the key assumptions, which were based on ATAGI advice. The reduction in infection captures the known effect that vaccinated people are less likely to catch the virus than non vaccinated people. And then once they’ve caught it, they are also less likely to transmit it. Overall those two effects lead to quite a big reduction in transmission of virus from vaccinated people. The combination of reduction in infection, and reduction in onward transmission assumed in the Doherty report is shown below for the two major vaccines used in Australia. That combination leads to an assumption of around 90% reduction in overall transmission for fully vaccinated people (even though 20-40% of them are still likely to catch the virus).

But modelling done in the UK is based on less optimistic assumptions – the table below shows the range of assumptions, but multiplying them all out, the 86%/93% effectiveness assumptions after two doses that the Doherty Institute has used are lower in the UK modelling at AZ – 71/81/84 or Pfizer (known as Comirnaty) 90/91/85. All of the UK assumptions are lower effectiveness than the Doherty Institute is using.

This article looks at some of the evidence from around the world feeding into these assumptions – it is not an easy thing to measure, as there is no random controlled trial going on. So what happens if we take the lowest of these UK assumptions? Does it make a difference to the modelling?

An 80% vaccinated population (on average) will reduce the Reff by 58% (80% times 90% (average of AZ/Pfizer) times 80% (proportion of the population that is eligible). So a Reff of 6 would become a Reff of 2.5. If the effectiveness instead was 71/85 (average of 78%) then the Reff would reduce by 50% – the Reff would become 3. That doesn’t sound like a big difference, but right now, the NSW outbreak is hovering around a Reff of 1.2/1.3 – if it was 0.8 instead, then cases would be going down instead of up. Or to put it another way, instead of vaccinating 80% of the adult population, the impact on the spread of the virus would need a vaccination rate of 92% of the adult population instead.

And while I’m here looking at vaccine effectiveness, I was curious to see what might be happening in NSW as vaccination ramps up here. Is it already reducing spread of the virus?

Probably, but it is important to note that vaccinations don’t work properly until around 2 weeks after the vaccination date. So on 25 August, we should look at the vaccination levels on 11 August. On 11 August, NSW had 24% of the adult population fully vaccinated, and another 24% of the adult population had had at least one dose. So the overall effect on vaccination levels on 25 August (using the Doherty Assumptions) would be 29% reduction in the Reff. Which suggests that the current Reff of around 1.2/1.3 would be around 1.5-1.7 without the current levels of vaccinations.

Rereading the Doherty report again reminded me of two key points:

- With the Delta variant, reducing spread of the virus relies heavily on things other than vaccinations – even at 80% of the adult population vaccinated, Covid19 will spread widely unless other actions continue – contact tracing, testing, isolation, and some lockdowns at high case numbers.

- The whole population needs to be vaccinated at the high levels recommended. If there is a subpopulation (eg right now the aboriginal population in Western NSW) that is vaccinated at lower levels than the population as a whole, then Covid 19 can still spread rapidly through that population no matter how well the whole population is vaccinated. The Doherty report makes this point directly:

-

Note that even for high coverage, late epidemics are observed, with associated severe outcomes, reflecting the ability for circulation in unvaccinated population subgroups, which are likely to be concentrated within communities and geographical areas. Further improvements in vaccine uptake would be needed to prevent these outcomes.

And if you are glutton for punishment, there are other models out there focused on Australia (here’s a sample of ones I’ve followed, but I’m sure there are others).

They approach the problem from different angles, but all of them reach similar conclusions:

- vaccination makes a huge difference to hospitalisation and death from Covid19

- without continuing other non-vaccination measures vaccination will not stop the spread of Covid19 by itself

- Severe lockdowns are still needed to control the spread of Covid19 until population level vaccination gets to quite high levels, and may continue beyond that depending on the pattern of spread.

Next I’m going to have a closer look at the modelling outcomes for hospitalisation and death – what levels of hospitalisation and death are we implicitly accepting with this approach to when restrictions are relaxed, and how variable could they be depending on the assumptions used?

Links

In this house we’ve taken to downing tools at 11am to watch the NSW press conference with the days numbers. So we’ve created a little gadget here(which is also on the front page of this blog) that uses a simple weekly exponential growth measure to project cases in the next 7 and 14 days. I’ve found it very educational – even for those, like me, who intellectually understand exponential growth, it is still a surprise to see it in action.

Periodically I look at countries with high vaccination rates that have opened up to see what might be coming for us. This article from the Financial Times is a good summary of what has happened in the UK after their so-called “freedom day”. Cases didn’t increase as fast as epidemiologists expected, and they think it is because the population as a whole didn’t immediately revert to pre pandemic behaviour; they were much more cautious.

Professor Robert West, a University College London psychologist and member of the government’s Scientific Pandemic Influenza Group on Behaviour, said his committee’s findings on how behaviour would change after the end of legal restrictions proved “decidedly pessimistic in retrospect”. West said the debate over freedom day showed there are “more than just two players — government and the general public”. “Other parts of our society — businesses, local authorities, regional governments — have stepped in, where the government has stepped back, to enforce some form of restrictions,” he added.

John Edmunds, professor of infectious disease modelling at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, said the Euros-driven spike in cases offered an insight into how far things still are from the pre-pandemic norm. “You could view [the Euros] as some sort of extraordinary event but I think that’s the wrong way to look at it,” he added. “I think what it actually is, is a glimpse into normal behaviour that we’ve forgotten. It was not that different to every Friday and Saturday night in a pub before the pandemic and you could see the immediate effect.”

And Singapore, which has been much more similar to Australia (but is now much more vaccinated) in its approach to Covid for the last 18 months is cautiously reopening to the world according to this article from Fortune.

Not that Singapore will allow life to return to normal. It is choosing to take it slow. First, it has set itself an unusually high bar for vaccination: It won’t begin to reopen until 80% of its population have been double-jabbed. By contrast, Britain lifted restrictions with about 65% fully vaccinated. Second, even when it reaches that threshold in early September, Singapore will reopen with a whimper rather than a bang. On Sept. 8, Singaporeans will be allowed to travel without quarantining on their return—but only to two countries with low rates of COVID-19, Brunei and Germany. For the time being, mask-wearing will remain mandatory, contact-tracing apps will remain in use, and restaurants will still have to abide by the 10:30 p.m. curfew.

And a nuanced article about public health responses in NSW, focusing on how spread can be reduced in workplaces, which doesn’t seem to get much commentary or questioning in NSW at the moment.

When we describe workplaces as melting pots, we mean they are places where people who don’t otherwise know each other are mixing, creating links among household and family networks that wouldn’t otherwise exist. If we want to prevent the household clusters that generate big numbers, we need to eliminate these “bridging” cases. Restrictions are not simply intended to ensure everyone stays at home so that nobody can possibly be infected. Their little-recognised goal is to reduce the mixing rate among people from different networks.

So far in New South Wales, the burden has been placed on the shoulders of workers in “LGAs of concern,” including a requirement to get swabbed every three days before leaving the local government area for work. But with Delta, a lot can happen in three days. To drive cases towards zero, strict limits must be applied to employers rather than employees.

Life glimpses

This week we decided to go “out” for dinner – we had a dinner at a different table in the house – with a dish cooked by each member of the family. That meant that the dessert was a ridiculously rich chocolate fondant truffle cake that my body is still recovering from. Here in Sydney, we now have to wear a mask any time we are outside the house (unless we are exercising) – I hear most of my readers exclaiming “about time!”. I suspect my daily walks with geekinsydney are going to get a bit shorter. And the current rain in Sydney means I’m realising a mask in the rain is more annoying still.

My cousins in New Zealand are also in lockdown – everyone seems a bit more tired of it all this time around, so not as much email banter as previously happened. I’m still clinging on to hope that my February 2022 trip that I’ve booked to NZ might go ahead… but luckily it is 100% cancellable (as all my trips are these days).

And another link – the IMDB reviews of the daily NZ Covid press conferences are a lot of fun. Made me want to see if someone could review our NSW current season?

This debut series from little-known studio, Beehive, portrays an eerie pre-apocalyptic dystopia that depicts a country battling to save itself from a deadly virus ravaging the rest of the planet….

All I can say is… WOW! Season 2 doesn’t just pick up where Season 1 left off… it EXPLODES into the middle of the action. No preludes, no warnings, just straight onto the white-knuckle rollercoaster we’ve come to love and fear in equal measure.

Bit of beauty

A picture from our recent zoom cocktails – premade negroni from one of the proliferation of providers available in Sydney’s lockdown.