Last week was the annual release of the Closing the Gap report. As the report describes:

In 2007, Commonwealth, state, territory and local governments made a commitment to work together to close the gap in Indigenous disadvantage. This led to the National Indigenous Reform Agreement, a significant step toward more coordinated action.

The first Closing the Gap framework outlined targets to reduce inequality in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s life expectancy, children’s mortality, education and employment. The commitment focused on delivering policies and programs across fundamental ‘building blocks’ as priority areas, which would underpin improvement. These were: early childhood, schooling, health, economic participation, healthy homes, safe communities, governance and leadership.

The Commonwealth Government has delivered an annual report on progress on Closing the Gap since the National Indigenous Reform Agreement was established.

As a fan of using data to drive action, it’s great that the government reports on progress every year, and has done for more than 10 years. Sadly, the outcomes being reported are generally the opposite of progress – more like a report on Opening the gap.

In the past I’ve blogged about the life expectancy measure a few times, never with particularly good news.And this year, true to form, the gap appears to have widened, rather than closed.

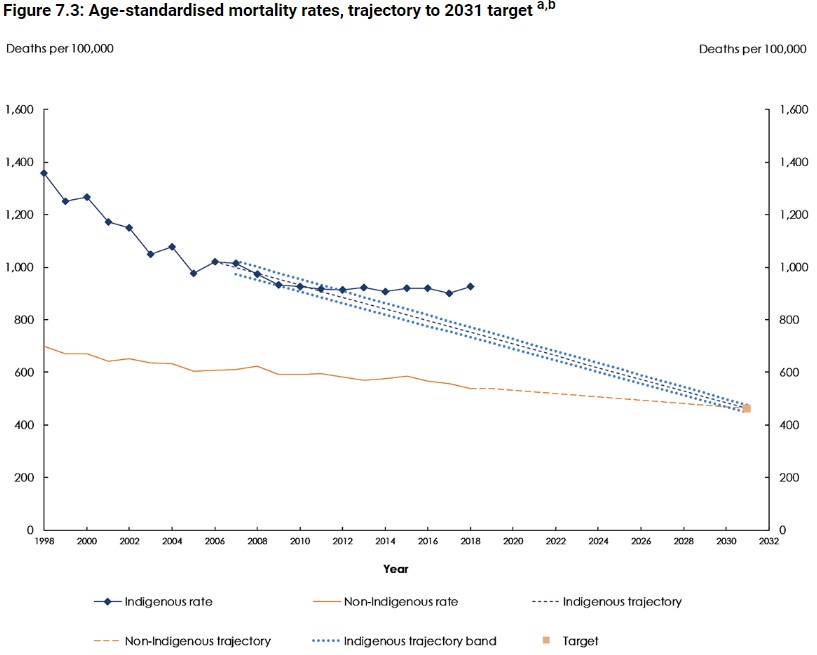

In 2018, there were 3,218 Indigenous deaths (1,780 males and 1,438 females).3 This was equivalent to an age-standardised mortality rate of 927 per 100,000—around 1.7 times the non-Indigenous rate (539 per 100,000). The Indigenous rate was not within the range required to meet the target (Figure 7.3).

The graph shows that the improvement in indigenous mortality rates levelled off just as the Closing the Gap measurement got started, and rates were actually higher in the most recent year of measurement. The graph shows age-standardised mortality rates rather than life expectancy as life expectancy is only calculated by the ABS every five years.

So in search of some slightly more positive news, I went looking at school attendance. The target for school attendance was to close the gap between indigenous and non indigenous school attendance in the five years to 2018.

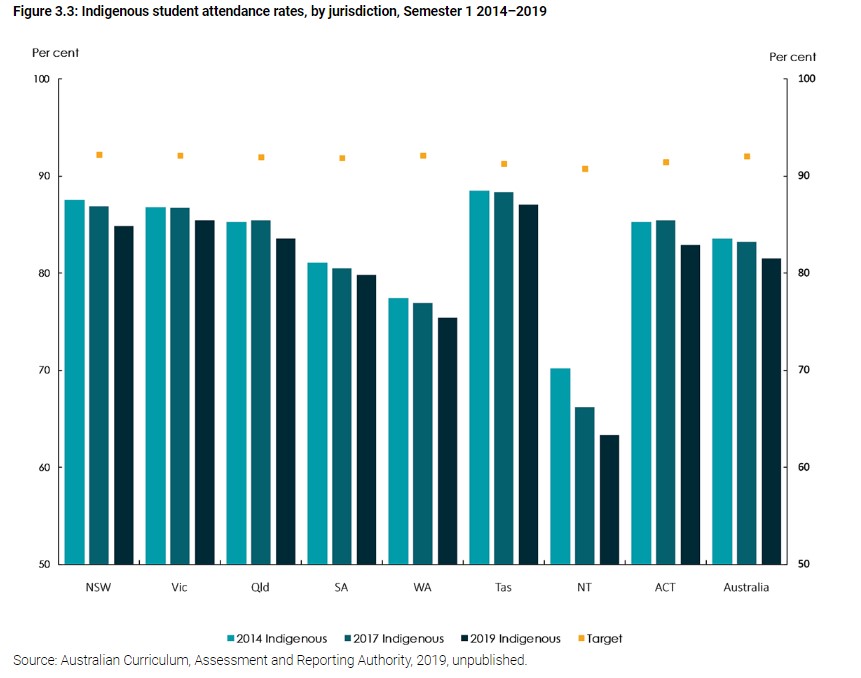

Sadly the school attendance percentage for indigenous students in every state and territory has declined between 2014 and 2019 (by an average of 2%). The graph below shows the specifics.

Overall, indigenous children in Australia attend on average miss almost a day a week of school (much more in the higher years of school, and in remote areas). By contrast, non Indigenous children attend just over 90% of the time (missing nearly 1 day an average per fortnight). It isn’t surprising that the specific measures later in the report on school outcomes are not as good.

The only saving grace in these statistics is that non indigenous attendance rates have also declined over the same period, although not by as much. But it can’t be a good thing that attendance for all students in Australian schools has declined by around 1.2% in the last five years.

The Closing the Gap report doesn’t report on potential actions or solutions (that isn’t its role). As it says:

School attendance is associated with a range of interrelated and complex factors.

To improve school attendance for indigenous children there are probably a range of underlying factors involving the school itself, the families that the children come from, housing situation, plus many more.

I’ve blogged about one factor before – one of the interrelated and complex factors is the level of school suspensions, which is much higher for indigenous children, with 12% of indigenous children having at least one school suspension each year, which of itself reduces school attendance, as well as probably leading to more absenteeism.

My focus on this particular statistic comes from my belief that a good education is important for everyone. A good education for our whole population (not just the “smart”or the middle class) is so important for the lives and economic future of everyone in this country. From these statistics, Australia’s education system in its broadest sense is not adequately supporting and educating our indigenous students. All of us in this country are worse off if a significant proportion of our population do not receive a good education.