How has Victoria’s crushing of its Covid19 second wave compared with others around the world?

This week everyone in Australia is celebrating Victoria’s success in smashing its second wave of Covid19. So how does Victoria’s experience compare with the rest of the world’s? Extraordinarily well. I’ve looked at every country in Our World in Data. And there are plenty that have managed to reduce a second wave of Covid19 to half or a third its original size. But most of those have had the virus come roaring back again even worse – once restrictions are eased again.

An example of this is three smaller European countries – Denmark, Croatia, and Serbia. (I should note that through this post, I’ve linked to graphs as well as embedding them – depending on how you read this, you may not be able to see the graphs without clicking the link). On 25th September, the Serbian government proudly pointed out that the risk of catching Covid19 was the lowest in Europe. But since then, the cases have grown six fold – from 10 per million people to 60 per million people, and Serbia has readied its field hospital in Belgrade for patients again, after it was key in July. You can see similar patterns in Denmark and Croatia, an increase in cases, after the summer break, a flattening and reversal of the trend, and then a much worse outbreak after restrictions were lifted again.

Other places worth looking at are Israel, and Iceland – places which successfully reduced the first wave, had a second wave, and have reduced it, but only to around 100 cases per million of population per day. Israel has reduced their cases substantially from the highs in September, but the cases per million people are still higher than Victoria was at its worst. And Iceland is still in the middle of a second wave and has just tightened restrictions on movement.

Our World in data doesn’t show states, but the graph of the whole of Australia is a good proxy at a country level for how much Victoria has been able to squash the curve. As I said in my last post, if you want to find countries doing well, you need to look at our part of the world. This graph shows Singapore, South Korea, Japan and Australia. Singapore has had the highest peak – peaking at around a rolling 7 day average of 160 cases per million per day – about the same as the levels Iceland and Israel are now at having reduced their second waves. And Australia has reduced their cases per million to the lowest level after a second peak – from 21 per million per day to 0.6 per million per day. For Victoria only, the peak was around 80 cases per million per day, down to the seven day rolling average now of only 0.5 per million per day, the lowest of the four countries on this graph.

It’s hard to see on this graph, as Singapore’s peak was so high, but Victoria has squashed their second wave curve better than any country I’ve been able to find in the data. You could argue, as this article does, that New Zealand and Vietnam have done better – although it depends on how you define a second wave – as those two countries got their virus under control almost too fast to define as a second wave. The key question, of course, is whether it will stay low once restrictions ease. But the examples of countries that have made it work show that the key is to get the number of cases to a low enough level that contact tracing and testing can work. And by staying the course with such a long lockdown, Victoria has given itself every chance of success.

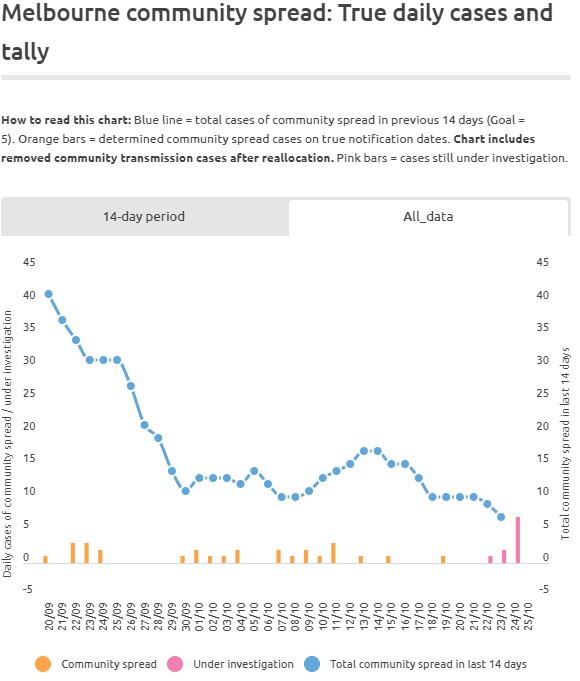

To show that, I’ve shown the graph of the key metric of how Victoria has got this wave under control – the number of unknown community transmission cases over the last six weeks. The line shows the rolling total of unknown cases over the previous 14 days.

To show that, I’ve shown the graph of the key metric of how Victoria has got this wave under control – the number of unknown community transmission cases over the last six weeks. The line shows the rolling total of unknown cases over the previous 14 days.

Making that curve flatten is hard work, and relies on people being tested, and being happy to share their movements with a contact tracer. It is a credit to the whole community of Victoria that such a long, intense lockdown held up well enough for both the testing and the tracing to work. As a contrast – in Israel, large groups in the community decided to ignore lockdown, and I’ve seen reports around the world of people refusing to tell contact tracers their movements.

Clear and consistent communication, leading to trust throughout the community in all of the public health measures is incredibly important, and easy to take for granted.

Everyone in Victoria deserves the rest of Australia’s thanks and congratulations, and good wishes as, from tomorrow, their restrictions are lifted and life becomes much closer to normal.

Links

This article from Wired looks at how the existing poor health of many populations around the world has contributed to Covid19’s toll.

A MASSIVE NEW accounting of the health of humans on Earth, collating and inferring stats on hundreds of diseases and injuries across 204 nations, has mostly good news. People are healthier, and they stay that way for longer. The bad news: That’s not true if those people are poor, are people of color, live in the United States, and there’s a pandemic. Then they’re screwed…

Overall, the things that kill the most people aren’t communicable diseases like Covid-19. The number-one killer worldwide is high blood pressure; number two is disease related to tobacco use. In fact, everything on the top-10 list is the same population-scale stuff that takes systemic change to fix. That’s air pollution; nutritional gaps that lead to diabetes, obesity, and heart disease; and alcohol abuse. Childhood and maternal mortality still sneaks into the top 10 worldwide, too….

But the really interesting breakdown is along economic lines. Lower-income countries are actually doing a better job of reducing DALYs [Death Adjusted Life Years] than middle- and high-income ones like the US. And the burden of illness in the US falls disproportionately on poor people and people who aren’t white. “In the United States, when you compare us to the rest of our peers—the countries who are very rich, similar to us—we do poorly,” Mokdad says. “Very poorly.”

Life Glimpses

This week I was in a room with more than 20 people twice! The art gallery to see the Archibald prizes (in time honoured fashion my favourite was not the winner) and to the Sydney Theatre Company’s first play after lockdown (Wonnangatta). The Archibald prizes had timed tickets, with a socially distanced queue, but very few people wore masks (which I found a little confronting, since it was the most people I had been in a room with since the 12th of March, and by a big margin). At the Sydney Theatre Company masks were compulsory, and the theatre was only 25% full – it was strange before the play started, but great to see live theatre again.

Bit of Beauty

This flower comes from one of our daily walks – I’m paying attention to the flowers the most I ever have this spring, and there are so many beautiful ones.

How do we communicate this effectively?

New Zealand went faster and harder in locking down in response to a small outbreak, so they didn’t even see a second wave at all.

On the other hand, of course, NSW has managed its own small outbreaks without having to lock down.

My sense is that there’s a magic daily number (and/or active total) beyond which contact tracing can’t be expected to succeed. And that number depends, inter alia, on the quality of the contact tracing team, the propensity of affected people to cooperate (isolate, get tested, tell the truth, etc) and the availability and speed of testing. And then there’s dumb luck.

I suspect that the magic number is higher in NSW than it was in Victoria, but I think we were also luckier. NZ simply didn’t leave it to chance at all.

Once you’ve blown through the magic number, it seems that you have to lock down. Get the transmission opportunities down and help the tracing team to get back on top. And then stay the course until you are safely below your magic number.

As a society, we are fortunate that we can afford lock-downs. We are also fortunate that we have a reasonably compliant population. Some of the latter comes from (or is supported by) clear and logical communication and leadership. What Dan Andrews (in particular) has done in that regard will one day be a case study.

Our near neighbours have also been reasonably compliant, with clear (or at least firm) leadership. And they have done well.

The “problem” with this approach? If you crush each outbreak (reasonably) quickly, then you have “clearly” overreacted to a minor issue. No-one (well, almost no-one) measures the lives saved, let alone all the other societal benefits of not having let Covid run riot.

So I return to my question. How do we communicate not only what a great job has been done in crushing the outbreak but also what the real benefits have been?

I do wonder if we had a rehearsal for being compliant with the bushfires over summer. Obviously a much more visible threat, but holiday makers being told to go home saw people leave and no demonstrations about limiting freedom that I am aware of . Perhaps an element of trust in expert advice was achieved and noted.

Great that you could enjoy some cultural activities. One for you and one for me.

I am surprised that at the Art Gallery it is not compulsory to wear a mask. Congratulations to Victoria

doing so well.

Here supposedly the numbers are coming down, the policy of the government as far as Covid 19 a is concerned

is chaotic. So many political parties pulling this way and that way, one I will try to explain it to you.

Love the flower, I think a garden near by has some. It is supposed to be autumn here, but it is hot during the

day, not much cooler at night.Love