With the delta variant widespread, Australia needs to aim for around 80% vaccination of the whole population before widespread opening of international borders to avoid lockdowns and unacceptably high deaths from Covid19, based on my use of The University of Melbourne’s Covid19 modelling. We could open up in a limited way at earlier levels (at least 50% of the population vaccinated), but to avoid frequent lockdowns, we would have to limit international arrivals until vaccination is close to population wide. And even when opening up happens, many of the non pharmaceutical measures (like masks, contact tracing, regular testing etc) we have grown used to since Covid19 came to Australia will still be with us.

Alan Kohler, in trying to work out next steps for Australia, quotes epidemiologist Tony Blakely (the lead author of the modelling research):

Professor Tony Blakely of the University of Melbourne explains that the new R0 number of COVID-9 is five (that’s the number of people one infected person infects, on average), which means that 80 per cent of people (four out of every five) have to be immune to prevent the virus from spreading.

But Professor Blakely added that because no vaccine is 100 per cent effective – Pfizer is 80 per cent and AstraZeneca 60 per cent – 90 per cent of people have to be vaccinated to achieve 80 per cent immunity.

So simplistically, population immunity can be calculated using the vaccine efficacy against spread, and the infectiousness of a disease. If we assume that the Delta variant has an R0of 6 (one person infects 6 others, in the absence of precautions – my reading suggests it is more like 6 than 5), and 100% effective vaccine, then 83% of the total population needs to be vaccinated. That’s the whole population, not just the adult population – so if you only vaccinate those over the age of 16, then more than 100% of them need to be vaccinated (or some children need to be infected rather than vaccinated) to get to population immunity.

But herd immunity isn’t just a magic on-off switch. The reason it works is that when someone becomes infected with the disease, if enough people are immune, there is no-one for them to spread the disease to. The standard population immunity percentages, though, depend on an even spread of vaccinations across all parts of the community. If there is a pocket of the community with very little vaccination (for example in Israel, the ultra-orthodox community was hesitant at the beginning) then a disease can still spread in that community if they all have contact with each other, even if the wider population is fully vaccinated.

If not enough of the community are vaccinated for population immunity, the spread of a disease will still be lower – each person will still spread the disease to fewer people, and so the non vaccination precautious (such as lockdowns, school closure, international quarantine) don’t have to be as strong to reduce the impact of the disease.

You can see this in the modelling done by the University of Melbourne team. The key message I took away from their work is that we shouldn’t think simplistically about a magic date or level of vaccination when all the restrictions disappear. Every intervention has its place, and the more people are vaccinated, the fewer restrictions we need for whatever our risk appetite is. There are a number of tools in the toolkit, and as we open ourselves to the rest of the world (and each other) each tool has its place.

- International borders – gradual relaxation of rules for lower risk countries

- International borders – gradual relaxation of rules for vaccinated people

- Home quarantine or hotel quarantine – home quarantine probably has more risk of escape than hotel, but could be reserved for lower risk people

- Lockdowns – loose or tight (the modelling has a long discussion about this – both the level of lockdown, and how quickly they are used in an outbreak)

- Social restrictions such as limits on people per room without lockdown

- Ventilation rules (common in Japan)

- Mask wearing

- Vaccination of our population

There also isn’t just one measure of risk appetite. Our primary measure might be the number of deaths from Covid19. But levels of hospitalisation, or number of cases (because they may lead to Long Covid and therefore long term disability) also matter. And we also might want to measure the percentage of time spent in lockdown – that’s a risk as well, as many people in Australia are all too acutely aware right now.

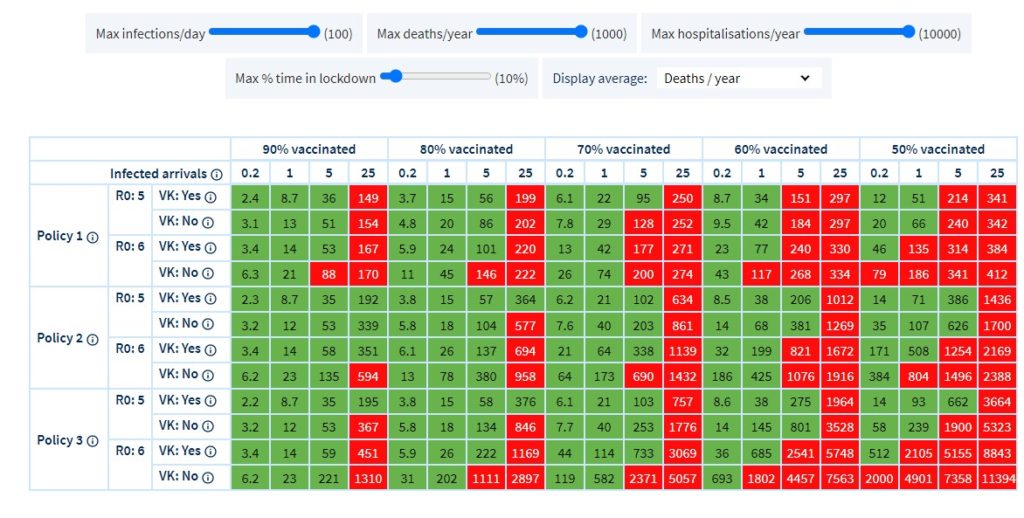

The Melbourne University modelling allows you to choose a variety of measures of risk appetite – such as infections per day, deaths per year, hospitalisations per year, and times in lockdown. The table above shows the numbers of deaths per year in Victoria (there are a bit over 40,000 deaths a year in Victoria) – on a wide variety of scenarios – with green where the outcome is lower than the risk appetite. Many of the red shaded squares are due to unacceptable levels of lockdown.

The conclusion I draw from this is that to return to the levels of international travel we used to have – even requiring full vaccination (which is about 5 infected arrivals a day) we need at least 80% of the whole population vaccinated. I’ve only looked at the lines with R0 of 6, and vaccination rates including kids, and we have to get to 80% of the population before most of the squares turn green – either because of the percentage of lockdowns or the annual deaths.

But in the details of this model are quite a few assumptions about public health policy that suggest that we are never returning to the normal we had in Australia in 2019. There will be a place for some form of international quarantine, mask wearing in some settings, contact tracing and isolation of cases, and most importantly, continued vaccination of the whole population against Covid19. And opening up will lead to some deaths from Covid19 – and if we open up before the population is fully vaccinated – some levels of lockdowns.

The modelling has almost too many options to play with, and if any of my readers are interested, go and have a look!

A word on assumptions – the model has some pretty rigorous analysis behind its assumptions (for vaccine efficacy, and hospitalisation and death rates, for example) which means I felt I could use it with confidence. They won’t all be perfect, but they gave me enough confidence to use the model.

Links

More about long Covid – The people running a long running British Intelligence test had a look to see whether Covid19 made a difference to results. And scarily, it did. Those people who had had Covid19 had worse scores than those who hadn’t, and the worse the Covid19 disease, the worse the cognitive deficit. For those who had been ventilated with Covid19, the Covid deficit was worse than a stroke.

Our analyses provide converging evidence to support the hypothesis that COVID-19 infection is associated with cognitive deficits that persist into the recovery phase. The observed deficits varied in scale with respiratory symptom severity, related to positive biological verification of having had the virus even amongst milder cases, could not be explained by differences in age, education or other demographic and socioeconomic variables, remained in those who had no other residual symptoms and was of greater scale than common pre-existing conditions that are associated with virus susceptibility and cognitive problems.The scale of the observed deficit was not insubstantial; the 0.47 SD global composite score reduction for the hospitalized with ventilator sub-group was greater than the average 10-year decline in global performance between the ages of 20 to 70 within this dataset. It was larger than the mean deficit of 480 people who indicated they had previously suffered a stroke (−0.24SDs) and the 998 who reported learning disabilities (−0.38SDs). For comparison, in a classic intelligence test, 0.47 SDs equates to a 7-point difference in IQ.

We can compare the likelihood of hospitalisation in each group to help understand the real-world effectiveness of the vaccines.

For the under 50s, we can see that 46% of the population is unvaccinated but they make up 87% of admissions. Meanwhile, 21% of the population is fully vaccinated but they make up just 4% of admissions. This tells us that the risk to unvaccinated people under 50 is 11 times higher* than the risk to vaccinated people.

For those aged 50 plus, we can see that just 5% of the population is unvaccinated but they make up 34% of admissions. Meanwhile, 79% of the population is fully vaccinated but they make up 43% of admissions. This tells us that the risk to unvaccinated people over 50 is 12 times higher* than the risk to vaccinated people.

Life Glimpses

As we settle into our lockdown routine, I’ve been exploring our local area by bike, running and walking. It has really struck me how many more bike riders are around than I remember from last time, particularly on very expensive looking road bikes. And then I realised that I’m seeing all those bike riders who can’t go to their normal rides because of the 10km limit. The popular spots of Akuna Bay, West Head, and others in the National Parks are out of reach of the people who live anywhere near me.

As it increasingly becomes clear that Sydney is locked down for a while, we’re tweaking our routine a bit. We’re pausing each day for the 11am press conference and look at today’s numbers, but trying not to spend too long watching it. And we’re eating a bit more takeaway than normal – both to support our local restaurants, and also to give ourselves some treats to look forward to.

Every local park I go to is as busy as I ever see them. I am hoping that people remember the beauty that exists in their own neighbourhoods when we are allowed further afield again. My own picture today is a great example of that. I thought I’d been on all the bushwalks within striking distance of my house, but this bit of bush is less than 1km from the Pacific Highway, and I’d never been down this path before.

Thanks so much for the work you do.

Shouldn’t we have had purpose built quarantine facilities though? That would have allowed for repatriation of Australian citizens while still protecting locals.

We still need them, don’t we? And will likely do so for some time to come. Hotel quarantine will become unviable when low-risk (vaccinated?) foreign visitors are competing for rooms with those whom we still want to quarantine.

If we ever find that we (temporarily?) don’t need these facilities, we can probably find another temporary use for them.

Yes, I agree with Richard, we definitely will still need them. The model I’ve quoted assumes that only fully vaccinated people are allowed back in, but there will always be people who can’t be vaccinated for various reasons who will need to come into the country.

I’m very keen on getting (almost) everyone vaccinated and opening up the borders, and I’m delighted that the vaccines seem to be remarkably effective. However, I don’t like misleading stats, even when they support my position.

First, it’s very disappointing to see actuaries incapable of distinguishing between “x times higher than y” and “x times y”. On the basis of the figures in that article, a random unvaccinated under-50-year-old in the UK has 10.6 times the hospitalisation risk of a vaccinated equivalent. That’s “9.6 times higher than”, not “11 times higher than”.

Secondly, and more seriously, although there is a bit of a caveat about age profile and co-morbidity, the potential impact of these factors is not mentioned. Nor is there consideration of the possibility that – especially among the young, where vaccination rates are lower – being vaccinated is strongly correlated with risk avoidance. So the conclusion is presented rather too definitively for my liking.

To illustrate this point, refer to the table in the article. If you take the total hospitalisations divided by total cases for (a) “unvaccinated” [not vaccinated or too recently vaccinated with first dose] and (b) fully vaccinated, you find that the hospitalisation rate for unvaccinated cases is 1.6% but the rate for fully vaccinated is 2.9%.

Surely the other time that we can open the borders is if covid gets out of control. “5 infected arrivals a day” doesn’t make much difference if we have 1000 new local cases. NSW is already at 400+ and growing exponentially despite lockdowns, testing, check-ins and contact tracing. I hope it declines but I’m increasingly pessimistic.

Yes, very good point, Tim, opening borders to a few more cases doesn’t make that much difference if there are a lot already in the community.