The Australian Government is inquiring into Long Covid and repeating Covid infections – the terms of reference are here.

I put in a submission, and I am sharing it here for the record.

The scope of my submission is a review of my understanding of the available data on the prevalence and severity of Long Covid in Australia (responding to item 3 in the terms of reference), and the potential impact of that severity on insurance in particular (responding to item 4 in the terms of reference).

3. Research into the potential and known effects, causes, risk factors, prevalence, management, and treatment of long COVID and/or repeated COVID infections in Australia;

4. The health, social, educational and economic impacts in Australia on individuals who develop long COVID and/or have repeated COVID infections, their families, and the broader community, including for groups that face a greater risk of serious illness due to factors such as age, existing health conditions, disability and background;

Summary

- There is a significant proportion of the population who have long term serious after effects from a COVID-19 infection. This includes both the constellation of symptoms often described as Long Covid, and also specific diseases which are more likely to occur after a COVID-19 infection.

- This extra source of disease in the population will lead to higher levels of short term and long-term disability, particularly in those of working age.

- The available data in Australia on the prevalence and severity of post COVID-19 disease is very limited, and the government should commission the development of a well-designed ongoing surveillance study from AIHW or other similarly appropriate body.

- An increase in disability in the population will also impact the insurance industry, which insures (via workers compensation, group superannuation and individual life insurance) people for disability.

- The insurance industry will expect to pay out higher claims, given the new potential source of disability in the population, which is likely to lead to higher premiums for those types of insurance in the longer term, and some potential for differential underwriting for those more likely to be exposed to COVID-19 disease.

- Support for the health sector in research, and support for practitioners providing evidence-based care for those with Long Covid, is likely to be beneficial for both those suffering the disease and the wider community, including the insurance sector.

Potential and known effects

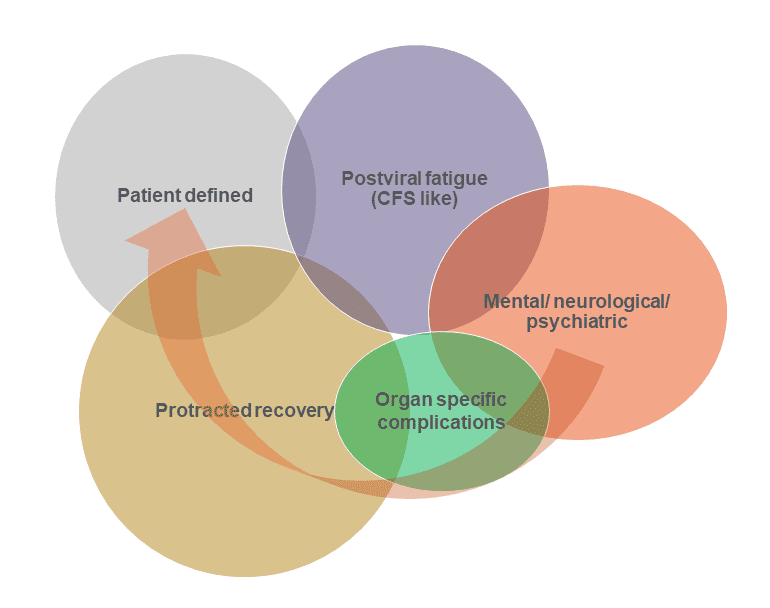

This article from Dr Achim Regenauer [1] is a summary of what we know so far. His outline of Long Covid can be summarised as:

It is likely that Long Covid has multiple COVID-19 related causes. They are likely to have overlapping systems, but potential separate causes:

It is likely that Long Covid has multiple COVID-19 related causes. They are likely to have overlapping systems, but potential separate causes:

- Postviral fatigue – a well-known phenomenon from many viral diseases, including the 1918 flu pandemic, and polio,

- Organ specific complications – there are documented examples of damage to specific organs post COVID-19 infections – eg this study of cardiovascular outcomes[2] shows heart damage is much more likely post a Covid infection than in patients with other respiratory diseases, and this study[3]looks increased risk of diabetes post a Covid-19 infection.

- Mental/neurological/psychiatric – this study[4]looked at long term nervous system consequences of COVID-19 and found a number of different neurological and psychiatric outcomes (this may be a subset of organ specific complications, but for the brain)

- Protracted recovery – COVID-19 is a complex disease, and it seems likely that some patients take a long time to recover;

- Patient defined – covering symptoms with as yet unknown causes that aren’t caught above.

Long Covid is commonly thought of as a wide variety of hard to describe but seriously disabling symptoms. However, the consequences of a COVID-19 infection can also include damage to other organs such as the heart, kidneys or brain, which may or may not be included in a measure of Long Covid. Someone who is diagnosed with cardiomyopathy, for example, may not be included in a statistical survey of those with Long Covid, as there are specific symptoms of a diagnosed non-COVID-19 disease.

Prevalence – available information

In Australia, there is little data available about Long Covid prevalence.

The UK and Australian statistics described below suggest that at any given time 0.5 – 1.5% of the workforce might be completely unable to work due to Long Covid, with another up to 5% having some restrictions on their ability to work due to lingering aftereffects.

Both of these studies rely on self-reporting, which is likely to:

- include some sufferers with non COVID-19 causes (if the symptoms spontaneously emerged for other causes post a COVID-19 infection), but also

- exclude some sufferers with specifically identified problems such as heart disease, which might be caused by COVID-19, but not necessary connected to a previous COVID-19 infection by the patient or their doctor.

Need for improved data

The lack of available information about Long Covid in the Australian population points to a strong need for a well-designed, ongoing surveillance study. Such a study would need to be at population level, and run by an appropriate body (such as the AIHW) to enable good information about the impact on the whole population from Long Covid. Such a study would support an understanding of the increased health needs arising from frequent population-wide COVID-19 infections. It would also help inform public policy decisions about the relative value of prevention of further COVID-19 disease compared with the public and private cost of Long Covid.

Such a study would also need to consider the prevalence of other organ specific complications such as heart damage and diabetes, which are not always included in the constellation of symptoms described as Long Covid.

Impacts on insurance

A disease such as Long Covid, which causes medium to long term disability, has economic costs, both to the disabled person, who is unable or less able to work and to society generally, as the person’s economic contribution (via work and taxation) is reduced or eliminated. The costs to the healthcare system, both private and public are considerable, and have been covered well in other submissions. However the cost of foregone income for those who are now less able or unable to work is also considerable, and I have focused on it below.

These costs are shared with society using a combination of public and private costs:

- Public cost – disability support pension (which requires quite severe disability for payment)

- Private cost via insurance – workers compensation insurance, disability income insurance, total and permanent disability insurance

- Personal cost – if a person is unable to work, or less able to work than previously but not eligible for any of the payments above, then their reduced income will be a personal cost

Insurance companies provide an important function in society in supporting people who are unexpectedly disabled. The disability support pension provides a basic safety net. However, income above the poverty line for disabled people unable to work will only come from insurance payments.

Challenges for insurers from Long Covid

Most insurance contracts for disability have a definition based on inability to work, rather than a specific diagnosis or injury. However, a diagnosis would be very helpful, particularly given the wide variety of Long Covid symptoms, and the differences in treatment, to make it simpler to work out the eligibility of the potential claimant, and to implement appropriate return to work measures. It may not be possible to have a single definition, but a suite of definitions based on diagnostic criteria would be helpful for patients, their medical practitioners and their insurers.

Insurers providing insurance for all forms of disability will need to consider whether the risk of disability in the working age population is sufficiently increased to require an increase in price, given the prevalence of Long Covid.

Insurers will need to consider whether it is feasible to increase the price specifically for those who have previously been diagnosed with COVID-19 and/or those who are more likely to be exposed to regular infections with COVID-19, as it is reasonably well established that each COVID-19 infection increases the lifetime chance of Long Covid. Other underwriting measures may also be considered. For example, workers compensation premiums for employers in sectors with high risk of COVID-19 (such as healthcare or customer facing roles) may be reduced for those employers providing safer workplaces with measures such as paid sick leave, ventilation of workplaces and mask wearing.

Health sector

In all cases, if the health sector can be supported with appropriate training and education, then those affected by Long Covid are more likely to be able to adapt their lives – both working and non working – to enable better participation in society and the workforce. The more information is available about the prevalence and seriousness of Long Covid (see data needs above) the better the health sector will be able to respond to the needs of patients.

Appendix – Prevalence Statistics

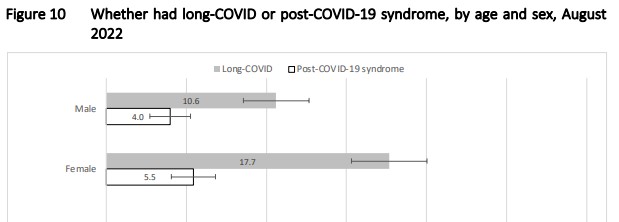

This Australian study by Professors Nicholas Biddle and Rosemary Korda is the first study looking at Long Covid prevalence specifically in Australia. They use survey data to estimate the prevalence of Long Covid in Australia, and particularly to measure the impact on people’s lives. The study looks at those who have ever experienced Long Covid (Covid symptoms for more than 4 weeks) or Post-Covid19 syndrome, and includes those who are now recovered.

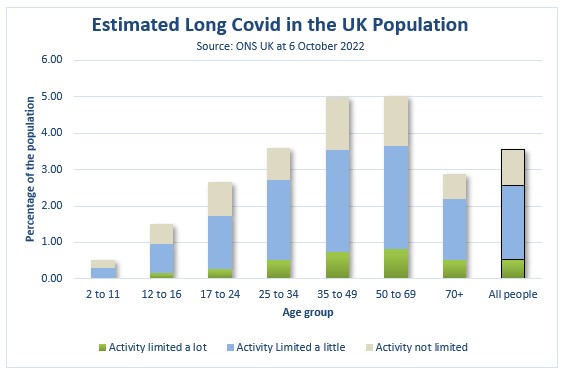

The total proportion of the Australian population who have ever experienced Long Covid (symptoms post 4 weeks) is 13.2% in total. A subset of these are those who have had Post COVID-19 syndrome (symptoms post 12 weeks that are limiting), which is estimated at 4.7% of all Australian adults. Looking at the current position, 13.9% of those who had had Covid19 at least 4 weeks before the survey now still had symptoms, which is 6.3% of the adult population. The ANU study asks whether the symptoms have led to limitations on day to day activities. Significantly, 22.5% of those with symptoms said that they limited their activities a lot”. That suggests around 1.5% of the adult Australian population currently has their activities limited a lot by Long Covid symptoms. This is significantly more than the equivalent number in the UK, even when only looking at adults (see more detail on the UK below).

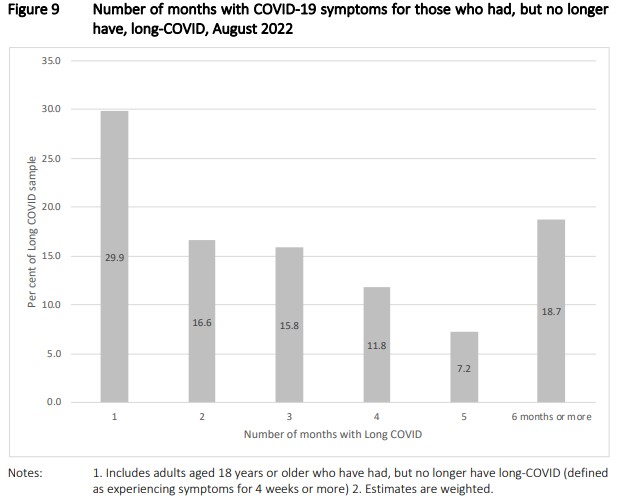

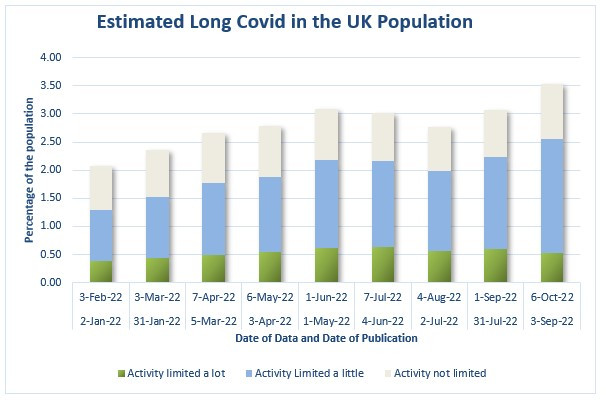

In the UK, the Office of National Statistics does a survey on self-reported Covid symptoms once a month. Respondents were asked “Would you describe yourself as having ‘long COVID’, that is, you are still experiencing symptoms more than 4 weeks after you first had COVID-19, that are not explained by something else?”, and then those that answered yes were further asked “Does this reduce your ability to carry-out day-to-day activities compared with the time before you had COVID-19?”.

The latest survey shows prevalence of Long Covid symptoms of 3.5% of the total population, with 0.5% of the whole population having Long Covid symptoms that limit their activity a lot. The timeseries of this survey shows the proportion of the population does fluctuate, but the overall proportion of the population with symptoms more than four weeks post COVID-19 infections is now higher than it has ever been (although the activities limited by a lot is slightly lower than it was a few months ago).

The difference between these two studies illustrates the difficulties of measuring Long Covid in a population, given the variety of symptoms. In addition, as noted above, there are also other types of disease with increased chances of occurrence in the population for those who have ever had COVID-19 – notably heart disease and diabetes. These other types of disease may not be included in either the Australian or UK identified population sets.

Nonetheless it is clear that COVID-19 leads to an increase in disability and death in the population as a whole, even after an arbitrary recovery period, whether it is 4 weeks or 3 months.

The UK and Australian statistics suggest that at any given time 0.5-1.5% of the workforce might be completely unable to work due to Long Covid, with another up to 5% having some restrictions on their ability to work due to lingering aftereffects.

[1] https://www.partnerre.com/opinions_research/new-long-covid-research-considerations-for-life-health-insurance/?utm_source=linkedin&utm_medium=social&utm_campaign=longcovid21&utm_content=en

[2] Long term cardiovascular outcomes of COVID-19, Nature Medicine 7 February 2022, Yan Xie, Evan Xu, Benjamin Bowe & Ziyad Al-Aly https://www.nature.com/articles/s41591-022-01689-3

[3] Risks and burdens of incident diabetes in long COVID: a cohort study, Yan Xie, Ziyad Al-Aly, in The Lancet Diabetes and Endocrinology https://www.thelancet.com/journals/landia/article/PIIS2213-8587(22)00044-4/fulltext

[4], 6-month neurological and psychiatric outcomes in 236 379 survivors of COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study using electronic health records, The Lancet Psychiatry by Maxime Taquet, Prof John R Geddes Prof Masud Husain, Sierra Luciano Prof Paul J Harrison https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanpsy/article/PIIS2215-0366(21)00084-5/fulltext

Links

Today’s Links are Long Covid only

Review of 10 Longitudinal studies from the UK

Reporting of symptoms lasting between 4–12 weeks ranged from 14.5% to 18.1%, and symptoms lasting 12+ weeks ranged from 7.8% to 17%. When restricted to reporting of symptoms that limited day-to-day function, as opposed to reporting of symptoms of any severity, proportions were lower: ranging from 3.0% to 13.7% for 4–12 weeks, and 1.2–4.8% for 12+ weeks.

Financial Times article on the economic effects of Long Covid

In the UK, 1.8mn people were out of work and not looking for a job due to illness in the three months ending April 2022, up by 269,000 or 17 per cent since the start of the pandemic. In the US, 1.35mn people were absent from work due to illness in May 2022, up 44 per cent on the pre-pandemic average for the same month, while 2.2mn had shifted from full-time to part-time work due to illness, a 37 per cent rise. The number outside the labour force who have a disability has jumped by 800,000 since the pandemic began, accounting for one-fifth of the 4mn labour force dropouts over this period.

Only a couple dozen doctors specialize in chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS). Now their knowledge could be crucial to treating millions more patients.

Atlantic article describing a common Long Covid symptom – Brain Fog

Of long COVID’s many possible symptoms, brain fog “is by far one of the most disabling and destructive,” Emma Ladds, a primary-care specialist from the University of Oxford, told me. It’s also among the most misunderstood. It wasn’t even included in the list of possible COVID symptoms when the coronavirus pandemic first began. But 20 to 30 percent of patients report brain fog three months after their initial infection, as do 65 to 85 percent of the long-haulers who stay sick for much longer.

Life Glimpses

Since my last Covid post, I’ve been travelling – 10 weeks in Spain, including walking the Camino de Santiago. I didn’t want to mention it here before going, lest I jinx the trip with some last minute Covid problems. But none of us caught Covid before or during our trip, and now we’ve been back a few weeks,

As travelling goes, it was pretty Covid safe – walking outdoors every day, and largely eating and drinking outdoors too, as we were very lucky with the weather and it didn’t rain at all during our walking. In Spain, masks are compulsory on all forms of public transport (and unlike here, people follow the rules quite well), but not many people were wearing them anywhere else.

And Spain is just starting a surge in Covid cases, just like Australia.

Bit of Beauty

Here’s a bit of beauty from Spain – sunrise over a small village called Torres del Rio in Navarre, northern Spain.

Very interesting article Jennifer, thank you. Glad you enjoyed Espana!