As Australians rally across the country to protest against mistreatment and deaths of Indigenous people, inspired by the week of protests following the death of George Floyd in the US, I’m comparing the statistics in the two countries.

It saddens me to find, as I expected (I’ve blogged about this before), that Indigenous people are treated overall much worse by the police and prisons in Australia’s judicial system than black Americans are by theirs. Adult Indigenous Australians are 11 times more likely to be in prison than a random Australian, whereas Black Americans are “only” three times as likely to be in prison as the average American. And while the death rates in prison for Indigenous and non Indigenous Australians are roughly comparable, the death rates in “police custody” (before getting to prison) are seven times higher for Indigenous Australians than all Australians. In the US, Black Americans are nearly twice as likely to be killed at the hands of police than the average American.

There are two main aspects of the justice system I’ve looked at:

- incarceration – are Indigenous [Australia] and Black [US] people more likely to be incarcerated than the population as a whole?

- deaths – are Indigenous and Black people more likely to die once they have made some contact with the justice system than the population as a whole?

Incarceration

In Australia, this graph, which comes from last week’s ABS analysis, shows the shocking difference between rates of imprisonment in Australia between Indigenous people and the totals for all Australians. The rates are per adult population, and show that in 2020, 4.7% of Indigenous men were incarcerated, compared with 0.4% of all men. For the population as a whole, those numbers are 2.6% of Indigenous people, and 0.2% of all people.

In the US, the graph below shows that while Black Americans are also over-represented in imprisonment rates, they are both less likely to be in prison than Indigenous Australians (1.5% compared with 2.6%) and also not as over-represented. Black Americans are three times as likely as the average American to be incarcerated, compared with Indigenous Australians who are 11 times as likely to be incarcerated.

Deaths in custody

In Australia, following the 1991 Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody, which investigated 99 aboriginal deaths in custody over the previous 10 years. In the US, the focus, following some appalling cases, has been on police killings. So the measures are somewhat different.

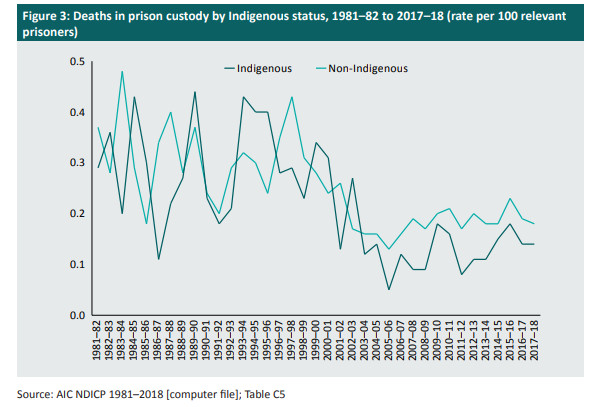

In Australia, this graph (from the National Deaths in Custody Report from the Institute of Criminology) shows that the rate of deaths in prison custody for Indigenous and non Indigenous prisoners has been reasonably similar over the past nearly 40 years. The overall average death rate over that period for Indigenous prisoners was 0.22% and for non Indigenous prisoners, 0.25%.

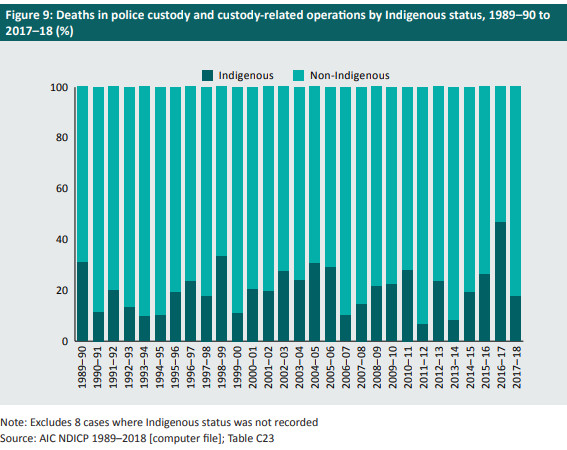

But the deaths in police custody and custody related operations [see the definition below], is a different story. Because these deaths are before any incarceration, they can’t be compared with a total prison population, the only comparative is the population as a whole.

This graph shows the proportion of those deaths which were Indigenous. Over the period tracked (nearly 30 years), there were 831 deaths in police or related custody, and 167 were Indigenous people. So 20% of the total deaths were Indigenous (and there were around 28 deaths per year in total, around 6 of them Indigenous). In the 2016 Census, 2.8% of Australians were classified as Indigenous. So Indigenous people are seven times as likely to die in police or related custody as the average Australian.

In the US, this group maps police killings every year, with their measure showing 2019 having 1,098 police killings in the US. Their definition is quite different, and would be expected to be a subset of the Australian definition (both definitions are shown below). In the US, 24% of police killings are of Black Americans. They are almost twice as likely to be killed by police as an average American.

Given the definitional differences, it isn’t really possible to compare the two statistics between the US and Australia, just the relativity within the wider population.

Definition of death in police custody in the Australian data:

- Deaths in institutional settings (eg police stations or lock-ups, police vehicles, during transfer to or from such an institution, or in hospitals following transfer from an institution).

- Other deaths in police operations where officers were in close contact with the deceased. This would include most raids and shootings by police. However, it would not include most sieges where a perimeter was established around a premise but officers did not have such close contact with the person to be able to significantly influence or control the person’s behaviour.

- Other deaths during custody-related police operations. This would cover situations where officers did not have such close contact with the person to be able to significantly influence or control the person’s behaviour. It would include most sieges, as described above, and most cases where officers were attempting to detain a person—for example, a pursuit.

Definition of police killing in the US data:

Police Killing: A case where a person dies as a result of being shot, beaten, restrained, intentionally hit by a police vehicle, pepper sprayed, tasered, or otherwise harmed by police officers, whether on-duty or off-duty.

I am not good at statistics. I read today’s and it is a worry. Cannot understand how does it happen,\what are we doing wrong. There is a big gathering in Rabin Square for Democracy, wanted to go as it is a around the corner.

Commonsense prevailed, lots of people, so many without masks, distance is probably forgotten.

Will fight for democracy at home. Love

Why do we have royal commissions if NO recommendations are implemented. Many issues out there. Surely this would be something Positive to do.

But if you look at the Deloitte Report on the 339 recommendations of the RCIADIC , you will find that only

6 % have not been acted upon.

It is just ” fake news” that ” nothing has been done”.

What has not improved is the offending and arrest rates for indigenous men.

As with most issues this is not as simple as emotively labelling things ‘fake news’.

The Deloitte Report was basically a desk research study which involved asking government departments what they had done: it looked at outputs rather than outcomes. So, many of the responses involved funding having been allocated to a body rather than outcomes being delivered through the application of that funding.

As an example, recommendation 251 says “That access to health care services and facilities, including specialised diagnostic facilities, in areas of Aboriginal population should be brought up to community standards.” The Deloitte report says this is: “… mostly complete as there has been increased access to health care services and facilities, as well as a greater number of staff devoted to providing care to areas with large Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations ” That response does not say that ‘access has been brought up to community standards’ – because, of course, it hasn’t – just that there have been increases.

A 2018 review of the Deloitte report by the ANU concluded that “… the scope and methodology of the Deloitte review mean that it misrepresents governments’ responses to RCIADIC, and has the potential to misinform policy and practice responses to Aboriginal deaths in custody.”

Other reviews of the implementation of the RCIADIC recommendations have been undertaken by various bodies from academics to law firms. The absolutely overwhelming conclusion is that the recommendations have largely not been implemented and the expected outcomes have not been delivered.

Just as a single randomly picked example, recommendation 60 is about the police services taking steps to eliminate violent, ractist, etc language. Clayton Utz’s report says: “Despite government self-reporting that claims full or partial implementation of Recommendation 60, this Report has been unable to locate any legislation, police procedure or guideline that explicitly responds to Recommendation 60 in its entirety”. That’s pretty well consistent across most of the analysis.

There have absolutely been some changes made in response to the RCIADIC recommendations. But those recommendations have not been fully, or even widely, implemented.

Just to reiterate : The ” myth ” that nothing , or very little, has been done in relation to the Muirhead recommendations is just that …. a myth.

But one repeated last week both in the SMH and on the ABC.

Please read what Jacinta Nampijimpa Price has to say on the recent BLM debate.

The BLM rallies which are a real threat to our Covid response are being justified , at least in part , by this myth.

Jennifer, my understanding is that indigenous people are overly represented in police custody relative to their share of the total population. Are you able to compare deaths in police custody of indigenous and non indigenous people as a proportion of total in police custody. Is this data broken down by state, gender etc?

Geoff, according to the research paper, there is no way to measure “those in police custody”, which makes sense when you think about it, as it includes those involved in sieges, car chases, and often when the police were trying to detain an individual. So all we can compare the numbers to is the whole population, so captures the combination of the likelihood of coming in contact with the police, and the likelihood of death once that occurs.

Deaths in the statistical analysis are broken down by a number of categories, the type of person, (age, sex, etc) the circumstances (for example motor vehicle chases), and the cause of death among other categories. I didn’t link to it, but the Guardian deaths in custody database has more heartbreaking detail than I cared to read on most of the indigenous deaths in custody since the Royal Commission.

Hi Jennifer,

With all due respect, Given the data shortages that you have outlined, and the data provided, it appears the only statement that can be made is that indigenous peoples are over represented in the justice system overall. Now that is an issue worth exploring and no doubt relates to economic disadvantages, substance abuse, domestic violence, cultural issues and an element of racism.

However, Suggesting they are ’treated more poorly’ in the justice system or by police cannot be inferred from that data provided (infact, the prison data presented shows there is no difference, actually slightly more proportional deaths for non indigenous Australian’s which you call out?) worse still, such a choice of language conjures far more nefarious images than prison system over representation and is totally uncorrelated to the data you provide. Overall, highly counterproductive?

If an an actuary can misrepresent data like this (however well intentioned) what hope do we have for policy makers to get it right?

Obviously a “non-actuary” needs to be careful in this debate , BUT :

* correctly , you mention that the death rate for indigenous prisoners in Australia is very similar to that for non-indigenous ( actually very slightly less ) ….. and the trend for both was down until about 2006

* what you seem to have missed is the vastly different rates of offending and being arrested. You make the alarming statement that ” indigenous people are 7 times more likely to die in custody than the average Australian ” without any reference to the relevant stat that they are much more likely to be in custody.

The big issue is why , and how well are young indigenous men being guided away from offending and incarceration ?