This week, I’ve been looking for evidence that the Australian justice system is racist against Aboriginal people. Given Indigenous people are locked up at 11 times the rate of non Indigenous people, racism seems likely to be at least some of the reason. Where statistics exist (and I’ve found some), they often show racism. But they are hard to find.

This week, I’ve been looking for evidence that the Australian justice system is racist against Aboriginal people. Given Indigenous people are locked up at 11 times the rate of non Indigenous people, racism seems likely to be at least some of the reason. Where statistics exist (and I’ve found some), they often show racism. But they are hard to find.

After my last post on Australian statistics on Indigenous deaths in custody, I’ve been asked whether we do have a racist justice system, or maybe its just that Indigenous people commit more crimes? How much really is bias in the system?

This line of argument is best encapsulated by Tony Abbott’s comments last weekend (described as incorrect in this article):

“Obviously the Indigenous incarceration rate is much higher than the general incarceration rate. That shouldn’t be so unless there’s evidence that courts are more likely to imprison Indigenous offenders than non-Indigenous offenders, and there is none,[my emphasis]” he told The Sun-Herald in his first substantive comments on the protest movement sweeping the globe.

“The higher Indigenous incarceration rate is a function of the higher Indigenous offending rate. It is absolutely tragic. But we know that when it comes to domestic violence and a lot else, this is much worse in Indigenous communities than most parts of the country.”

Indigenous incarceration rates that are more than ten times higher than population incarceration rates don’t, of themselves, prove bias in the system. They are very strongly suggestive, but they aren’t proof.

So this week I’ve been looking for proof. This article in the Guardian describes the data problems much better than I could, but despite a number of the Royal Commission recommendations being about better data, it is still very hard to find.

Despite the ramifications of over-policing, there remains a paucity of data, publicly at least. Most police forces do not release detailed breakdowns of their interactions with Indigenous Australians, NSW being a notable exception.

In Victoria, despite a commitment to begin mandatory recording of ethnic appearance descriptors in police interactions with the public, the force has refused to make the data public. In a statement this week, Victoria police told the Guardian there was “considerable community concern and risk associated with the reporting of ethnicity data”.

It is indisputable that an Indigenous person is worse off economically, educationally, and health wise than a non Indigenous person in Australia. That’s why we have Closing the Gap targets, and some of those Gaps are large, with life expectancy implicitly being a summary of many of the health and economic gaps:

In 2015–2017, life expectancy at birth was 71.6 years for Indigenous males (8.6 years less than non-Indigenous males) and 75.6 years for Indigenous females (7.8 years less than non-Indigenous females).

So how much of the difference in statistics for Incarceration and deaths in policy custody come from the underlying disadvantage of Indigenous people (which is probably also partly due to systemic racism), and how much comes from further racial prejudice in the judicial system?

I’ve been looking for evidence this week. It is hard to find. And not just because the judicial system appears reluctant to release statistics. The ideal statistical evidence would be a measure of the actual crimes committed by all Australians (of all racial groups) and then a comparative look at the progress of each group through the judicial system – from initial attention from the police, to being charged with a crime by police, to being convicted of a crime, and then the level of sentencing. Those first two steps of initial attention and being charged, are by their nature, almost impossible to find an underlying population level of statistics.

- Initial attention from the police – if we are looking (for example) at public drunkenness (which is a crime in Queensland) – without a measure of all the people who are drunk in public, it is impossible to be definitive about whether Indigenous people are more likely to be charged with it. Given how few non Indigenous people are arrested at sporting events for public drunkenness, I find it easy to believe that Indigenous people are disproportionately targeted for this offence. But nobody is sitting in public places counting the people who are drunk in public to work out the proportion of Indigenous and non Indigenous drunk people who are arrested.

- Being charged with a crime after coming to police attention – similarly unless there is public data tracking all the interactions the police have, by Indigenous status, it is very difficult to track whether someone who has a conversation with police is more likely to be charged if they are Indigenous, rather than not Indigenous.

Here’s the limited range of evidence I’ve found so far:

- NSW police let nearly four times as many non Indigenous as Indigenous offenders off with cautions after being caught with small amounts of cannabis

The data shows police were four times more likely to issue cautions to non-Indigenous people. In the five years to 2017, only 11.41% of Indigenous Australians caught by police with small amounts of cannabis were issued cautions, compared with 40.03% of the non-Indigenous population.

- While non-Indigenous people had a similar conviction rate for drug offences, evidence suggests Indigenous people receive harsher sentences, for example this analysis of data in NSW for women convicted of drug offences:

A global report prepared for Penal Reform International used Bocsar data from 2013 to 2017 to find Indigenous women were more likely to receive harsher prison sentences for drug possession offences, “including triple the rate of prison sentences”.

- This article looks at strip searches in NSW and concludes that they are disproportionately of Indigenous people:

Twelve per cent of strip-searches in the two year period were Indigenous people, even though they only make up a little more than three per cent of the state population. It included one 10-year-old and two 11-year-olds.

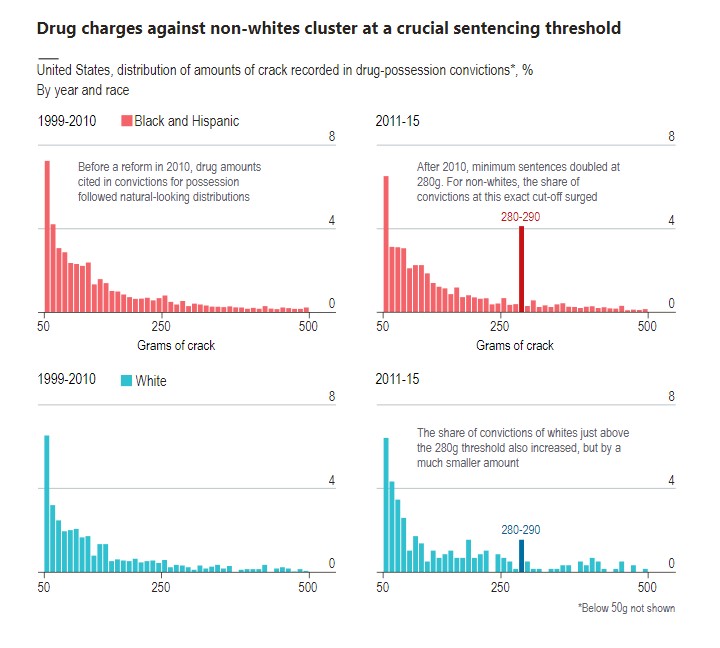

And this article from the Economist shows a similar example for the US (where there is much richer data available):

You don’t need a degree in statistics to believe that racial disparities plague American law enforcement. Of every 100,000 black adults, 2,300 are incarcerated—five times the rate for whites. This gap is not proof of discrimination: blacks could be five times as likely to break the law.

The graphs in this article show one study that The Economist quotes on how prosecutors use cut offs in the legal sentencing rules disproportionately to drive higher sentences for Black and Hispanic drug convictions.

Mr Tuttle finds that only a minority of prosecutors (around 20-30%) display this bias. These officials tend to work in states with above-median rates of searches on Google for racial slurs, suggesting racism is more common in their regions. In other states, “bunching” at 280-290g did occur, but affected blacks and whites equally.

An incarceration rate for Indigenous people 10 times higher than non Indigenous people seems very likely to indicate racism in the system. And it does exist. Several specific examples show racism does exist for particular police interactions and crimes. But statistics aren’t well kept, or available, and even if they were, not all aspects of the stages of the justice system are amenable to statistical analysis.

Thanks, Jennifer,

Well done on taking on this little challenge. One would have thought that there would be facts to support (or otherwise) Tony Abbott’s claim. It is disappointing that evidence is hard to find and I hope that it is not deliberate. In any event, your indicators are helpful and I hope that more evidence comes to light. I will share this with a couple of contacts and see what we can find….

The facts and figures are frightening. Will we, as humans, ever learn ?

Love

Thanks for this. Many figures quoted don’t tell the whole picture when comparing indigenous to non indigenous numbers. If things are to be managed better, pin pointing where in the process different treatment is given needs to be identified.

An incarceration rate of 10 times higher ” seems very likely to indicate racism in the system “.

Well ….. perhaps. To me , that is a long way from proof.

It is vital not to conflate the US and Australian situations.

What it DOES likely prove is that offending rates are very different in the 2 populations.

Why would this be ?

Why would the 5 indigenous Townsville teenagers ( ages 13,14,14,15,17 ) be travelling at 120 km/hr

at 4.30 am recently in a stolen car ? ( No police pursuit. ) ( All but the driver died. )

Will his incarceration be due to racism in the system , or would a much bigger issue be inadequate parental care

and an environment where disrespect for the law starts early, with terrible consequences ?

If these black lives matter , should there not be an uproar over this ? But no, most ( ?all ) of the early reports did

not mention their background.

And remember than the greatest chance of physical danger to an indigenous Australian comes from another indigenous person…. a much greater danger. And the commonest reason for incarceration is violence against another indigenous person. That is a pretty significant element to be considered in all this.

Please read Jacinta Nampijinpa Price from CIS.

Please note : we know that not all police are saints , but that is not the main element to this sorry tale ( IMHO).

And before using a phrase such as ” i find it easy to believe that indigenous people are disproportionately targeted for this offence “, I would suggest some work experience with the Police any pension night in Bourke , Brewarrina,

Walgett etc . Walk a mile in those shoes, and see how easy a job it is .

I’m not going to respond point by point to this comment, but I can’t let it slide either.

An incarceration rate of 10 times higher for Indigenous compared with non Indigenous people either indicates racism somewhere in the system, or it indicates that Indigenous people are inherently more criminal than non Indigenous people. I don’t believe Indigenous people are inherently more criminal than non Indigenous people.

It is possible, as you seem to suggest, that the racism only exists in setting up the poorer (on average) financial and family situation in which Indigenous people are born and brought up. If we broaden our search for places where racism can be identified in society as a whole, it is easier to find them. A specific example (not from the justice system) – my family has stayed at a hotel in Australia which explicitly admitted to us (white people) that they did not allow Aboriginal people to stay there. Here is an article with more examples.

But it is difficult to see the mechanism to end up with the outcome that while broader Australian society has systemic racism leading to poor outcomes and criminality, the police and the judicial system treat Indigenous people scrupulously fairly at all times. It seems much more likely that there is systemic racism across society in this country, and that leads to poorer outcomes for Indigenous people in education, employment, and yes, the justice system. Each aspect of the discrimination involved in all of those aspects is likely to combine to lead to the incarceration rate being 10 times higher for Indigenous people that we see in the statistics, which in turn leads to disproportionately more Indigenous people dying in custody. All of these aspects should be tackled, and this is why the recommendations of the Royal Commission into Aboriginal deaths in custody had 339 wide ranging recommendations, starting with very specific ones about custody arrangements, and moving outwards to many aspects of the treatment of Aboriginal people in Australian society as a whole.

The final recommendation was this one:

I don’t think anybody could say that this recommendation has yet been met in the last nearly 30 years (without a very inadequate definition of best endeavours). Right now, nearly 30 years later, the adoption of the Uluru Statement from the Heart would be a good start.