What does a 1 in 1000 year flood mean? Something labelled that way is now much more likely to happen than 1 in 1,000, as rainfall becomes both heavier, and more intense because of climate change.

What does a 1 in 1000 year flood mean? Something labelled that way is now much more likely to happen than 1 in 1,000, as rainfall becomes both heavier, and more intense because of climate change.

As a massive wet weather system batters the eastern coast of Australia, with (so far) $900m insurance claims, the Premier of NSW has described it as a 1 in 1,000 year event. My favourite response to this came from one of our satirical newspapers The Shovel:

Politicians and media have labelled the devastating floods in Queensland and NSW a once-in-one-hundred year natural disaster, the eighteenth once-in-one-hundred year natural disaster in the past year.

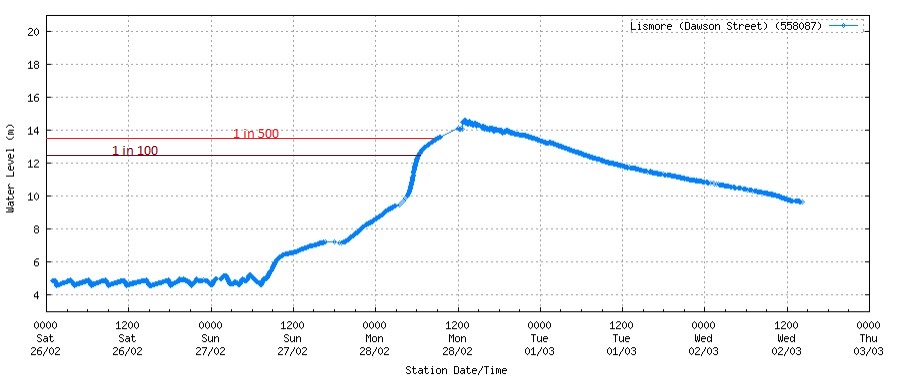

The Premier’s 1 in 1,000 statement was likely derived from a comparison of the peak of the Lismore flood with the 2014 Lismore floodplain management plan, where probabilities are placed on different heights of the river. The actual height of the river, according to thie graph below, was around 14.5m, and you can see the heights that the plan suggested were 1 in 100 year and 1 in 500 year events. Superficially that does make it appear that this was a 1 in 1,000 year event. But it does seem that we’ve been having 1 in 1,000 year events every few years. So what’s happening?

The flood plan was based on history. That history only went back to 1870, so included around 150 years of floods. It assumed in setting the probabilities, that the likelihood of flood hadn’t changed in that time – so no change in climate.

The flood plan was based on history. That history only went back to 1870, so included around 150 years of floods. It assumed in setting the probabilities, that the likelihood of flood hadn’t changed in that time – so no change in climate.

The climate scientists have told us that the likelihood of wet weather increases with higher temperatures. This report from Australian insurer IAG summarises the current Australian knowledge:

Extreme precipitation can intensify significantly with climate change, even in regions that experience drying on average. The more extreme an event is (i.e., the more intense and less frequent), the more its rainfall rate is likely to change in the future. A study of trends in Australian hourly and daily rainfall from the period 1966-1989 to 1990-2013 showed daily rainfall increased at around 7% per degree of warming. Emerging science also confirms that intense rainfall rates are increasing. These rates across southern Australia have increased nearly 14% per degree of warming, and 21% for the tropical regions.

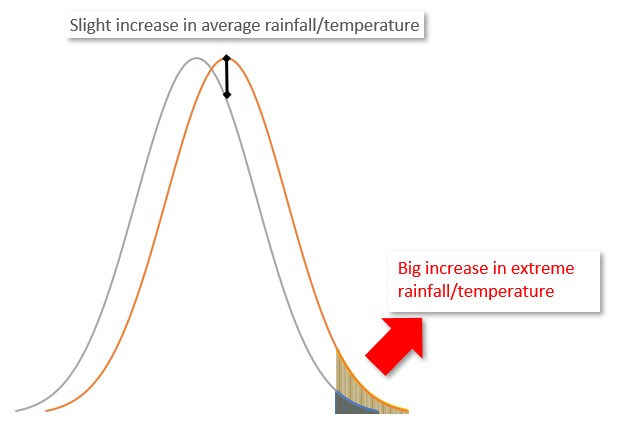

Basically, both the average rainfall, and the level of variability of that rainfall are likely to increase. So something that had a 1 in 1,000 chance of occurring would happen more frequently. Intuitively, you might think that if the average rainfall goes up a little bit, so does the chance of a big flood – maybe from 1 in 1,000 to 1 in 900? No. The extremes of the distribution become MUCH more likely. If the distribution is normal, that 1 in 1,000 flood will be five times more likely with a small increase in the mean. And the science tells us that the variability will also increase, which would increase the chances of that flood even more.

Weather modelling is very difficult, particularly extremes. But what happened this week in the East Coast of Australia was much more likely to happen now, after we have changed the climate of Australia by increasing average temperatures by more than 1 degree Celsius, than it would have been over the past 150 years that the flood planning was based upon.

Ironically, this flooding happened in week the IPCC latest report was released. This article is just one of the many reports about the unprecedented impact. Compare the two reports –

The IPCC’s final conclusion:

Climate change is a threat to human well-being and planetary health. Any further delay in concerted anticipatory global action on adaptation and mitigation will miss a brief and rapidly closing window of opportunity to secure a liveable and sustainable future for all.

and the newspaper article from country New South Wales:

In Lismore we have experienced floods forever. But this is not a flood, this is a catastrophe. This is extreme. This is a giant, angry river in the sky. This is climate change. If you had a flood plan – which everyone on flood-prone land does, especially since 2017 – it was meaningless. We have the 1974 flood imprinted in our cultural fibre. It was the biggest flood. There are markers on power poles all round town. These are the floods of the past. They are not the floods of today, the floods of climate change.

and you can see a clear link from the IPCC report about planetary climate change to this experience on the ground. The IPCC’s summary for Australasia sums it up:

Ongoing warming is projected, with more hot days and fewer cold days, snow and glacier retreat, sea-level rise, and ocean acidification (very high confidence). More extreme fire weather is projected in southern and eastern Australia (high confidence) and over northern and eastern New Zealand (medium confidence). Heavy rainfall intensity is projected to increase [my emphasis], with more droughts over southern and eastern Australia and northern New Zealand (medium confidence).

Bit of Beauty

Today’s bit of beauty is some fossil fuel infrastructure from my local area – a derelict coal wharf in the foreground, and an oil terminal in the background. That oil terminal will have to become derelict soon if we are to avoid even worse climate outcomes.

Thanks for this, Jennifer.

So we need to advance the debate around how probabilities of flood are calculated, pushing for trends in the mean and the volatility of rainfall to be taken into account.

While we’re about it, there are several other applications for better education of the public about probabilities. For a nation of gamblers, we’re very bad at understanding risk, not only in relation to flood but also (for example) in investment.

Meanwhile, thanks for the photo from the Coal Loader. When your hope comes true, there may be a boom in house prices in Greenwich!

Jennifer,

The “bible”, for those involved with designing structures that cope with this, is https://arr.ga.gov.au

Regards,

JBean

Thanks JBean, from a quick dip into it that looks fascinating. Interesting so far just for the chapter for how to express risk for users of flood reports, which is much more nuanced than the headline discussions I’ve seen so far.

Yes, the hydrologists and civil engineers were scratching their heads.

Problem with ARR is that meteorologists keep observing the weather and then change the probability of the rainfall intensity and duration over a given (fixed) catchment.